The Best Dark Love Poem I Ever Read

It was scrawled on a napkin by a sex worker in a Downtown LA diner at 3 AM.

Her real name was Sonia, which I knew because we’d grown up together in the same circle of high school friends.

“I’m not a professional writer like you or anything,” she said, sliding the napkin over so I could read what was on it. “But getting thoughts like these outta my mind keeps me sharp.”

I’d hope my heart break before my heart breaks

Love is just slow suicide with a witness

I’ve cried after reading certain pieces of poetry; I’ve also been moved to change the course of my life by others.

But nothing's stayed with me like those words on that napkin.

Because they came from someone who'd been broken by love.

And I'd been broken in much the same way.

I sold and did cocaine by the time I was 14. And at 19, I was overdosing on heroin in my girlfriend's arms. Love and destruction were inseparable in my world long before I discovered poetry could make that pain beautiful.

See, most articles about dark love poetry give you the same tired list: "The Raven," "Annabel Lee," maybe some Sylvia Plath if they're feeling adventurous. They'll explain how these poems explore "themes of obsession, pain, and loss" like they're reading from a high school textbook.

But they never tell you WHY we write these words down in the first place. Or why you can't stop reading it at 2 AM when your heart reminds you of its power to paralyze.

Dark love poetry isn't about Gothic castles or dramatic death scenes. It's about the moment you realize you're destroying the thing you love most. It's about loving someone who's already gone; whether they're dead, addicted, or just dead to you. It's about the specific weight of a silence after someone says they don't love you anymore.

I know because I've lived it. I've written love letters to women who would only ever see me as a wallet, or, even worse, they only saw me as a way to keep themselves entertained. I’ve watched entire portions of my family devoured by addiction and mental illness. I've watched love turn to violence, devotion turn to obsession, and promises turn to psychiatric holds.

And through it all, I wrote.

I attempt to find the lessons of growth or healing in my writing, but no matter what, the darkness never really leaves. It just becomes another color on your palette. Another tool in your arsenal. Another way to connect with others who've been where you've been.

So let me take you deeper than any AI-generated overview or academic analysis ever could. Let me show you what dark love poetry really is.

Not just the what, but the why and the how.

Because if you're here, reading this, you already know:

The darkness chooses you. Poetry just gives it a voice.

***JUMP TO SECTIONS: You can click the bracketed links below to navigate back and forth through this very hefty guide.***

// [What Is Dark Love Poetry?] // [The Psychology of Dark Romance] // [Famous Dark Poems] // [Death & Love Poetry] // [Modern Dark Poetry] // [Write Your Own] // [Why Now?] // [Curated Collection] // [Final Thoughts] //

Section 1: What Is Dark Love Poetry? (Beyond the Gothic Clichés)

// Word Count: 650 Words // Reading Time: 2 Minutes //

Let's get something straight: dark love poetry isn't just regular love poetry wearing black eyeliner.

A cursory Google search will tell you it "explores the complexities and shadows within romantic relationships, often delving into themes of obsession, pain, betrayal, and the darker aspects of human nature." That's like saying heroin is a "pain management solution." It's technically accurate, but it misses the point.

Real dark love poetry is what happens when love stops being pretty and tells the truth about the people we cherish and the hidden truths within us.

The Academic Definition vs. The Street Definition

Academia wants to categorize dark love poetry as a subset of Gothic romanticism, complete with supernatural elements and doomed lovers. They'll point to Poe's ravens and Browning's murders and call it a day.

But I learned my definition in rehab, watching a 45-year-old carpenter write poems to his dead wife on the back of AA meeting schedules. No vampires. No haunted castles. Just a man trying to apologize to a ghost for choosing vodka over her, every single day for twenty years.

That's dark love poetry: the documentary evidence of love's crime scenes.

Why Google's Overview Only Scratches the Surface

The search results you see focus on the symptoms, not the disease. They list characteristics like:

- Obsession and possession

- Pain and suffering

- Supernatural elements

- Forbidden love

- Destructive nature

Sure, these elements appear in dark love poetry. But listing them is like describing a gunshot wound by the color of blood. You're missing the bullet, the trigger, the finger that pulled it.

Dark love poetry emerges from three specific sources:

- Love interrupted by death (actual or metaphorical)

- Love corrupted by mental illness, addiction, or trauma

- Love revealed as delusion or projection

Everything else—the Gothic imagery, the dramatic metaphors, the haunting refrains—that's just decoration on the coffin.

The Difference Between Performative Darkness and Authentic Shadow Work

Here's how to spot fake dark poetry: it tries too hard.

Real darkness doesn't need to announce itself with skulls and roses. It shows up in the mundane details. Like an ex of mine, who once wrote to me: "You only try to love me when I'm dying." Seven words that cut deeper than any Gothic novel.

Performative darkness sounds like this:

"My heart is a cemetery where dead roses bloom in the moonlight of your absence..."

Authentic darkness sounds like this:

"I still set your place at dinner / six months after the funeral / the kids think I'm crazy / but it's the only time / I don't eat alone"

See the difference? One is costume jewelry. The other draws blood.

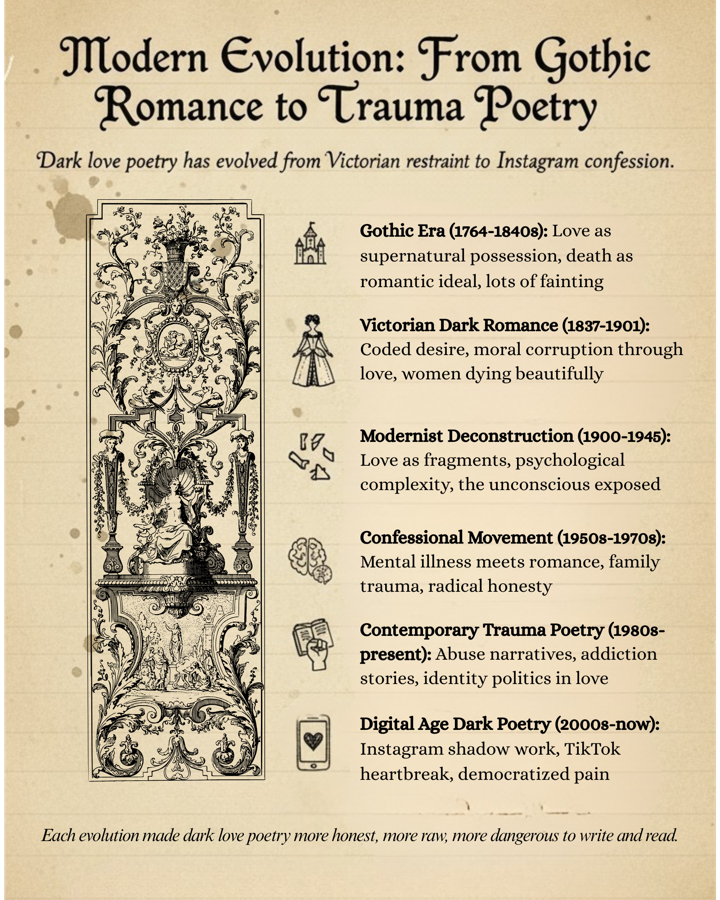

Modern Evolution: From Gothic Romance to Trauma Poetry

What Dark Love Poetry Really Does

At its core, dark love poetry serves three functions:

- Witness - It documents what love looks like when the lights go out

- Warning - It shows others the cliffs before they jump

- Healing - It transforms private pain into shared understanding

When I write about the moment I found out my friend was found in the trunk of a car that had been set on fire, I'm not glorifying darkness. I'm mapping it. So others can find their way out.

Or at least feel less alone in it.

That's what separates real dark love poetry from its Gothic cosplay: purpose. We don't write about darkness because it's aesthetic. We write about it because it's true. Because someone needs to say that love can kill you—literally or spiritually—and that's still not a reason to stop seeking it.

My friend Sonia, the sex worker who wrote her words on that napkin? I found out later she'd been married once. Her husband killed himself after she relapsed and left him for life on the streets. She wrote those lines not to posture: it was a page from her autobiography.

That's dark love poetry: the truth you can only tell after midnight, to strangers, in language that burns the page.

Section 2: The Psychology of Dark Romance (Why We Crave the Abyss)

// Word Count: 2,200 Words // Reading Time: 9-11 Minutes //

I once asked my therapist why I kept falling for women who were almost guaranteed to hurt me. It was a cocky rhetorical question. I thought I knew the answer, but she caught me off guard and said, "Because you're trying to complete an unfinished story from your childhood."

"That's oversimplified,” I said. “I'm mostly attracted to the chaos. Which is becoming less of a thing as I get older."

We were both right.

The human brain is wired for pattern recognition, and nowhere does this impact us more profoundly than in matters of love. We don't just fall for people—we fall for familiar forms of pain. Dark love poetry exists because it maps these patterns, giving language to the compulsions we can't shake.

Neuroscience of Heartbreak and Obsession

Let me break down what's actually happening in your brain when you read Plath's "Mad Girl's Love Song" at 3 AM:

Your brain processes romantic rejection the same way it processes physical pain. The anterior cingulate cortex—the same region that lights up when you break your arm—goes haywire when someone breaks your heart. This isn't metaphorical. The pain is literally real.

But here's where it gets dark: your brain also releases dopamine during romantic uncertainty.

That's right. The same neurotransmitter that made me chase cocaine and benzos also makes you chase unavailable lovers. The brain rewards pursuit, not capture. We're chemically programmed to want what hurts us.

This is why dark love poetry feels more "real" than happy love songs. It's not just emotional preference—it's neurological recognition.

Your brain identifies the pain patterns and whispers, "Yes, this is what love actually feels like."

Attachment Theory and Dark Poetry

My grandmother who used to sell me drugs? Classic disorganized attachment. She'd hug me with one arm while pocketing drug money with the other. That paradox—care mixed with harm—became my template for love.

But here's the thing about attachment styles: they're not fixed sentences.

I spent years ping-ponging between anxious and avoidant—desperately needing connection while simultaneously sabotaging it. Classic disorganized attachment, with a side of "I'll leave you before you leave me" and "Please don't go but also get away from me."

After almost a decade of analytical psychology, proper psychoanalysis, and consistent trauma-based healing modalities, something shifted. Not overnight—healing rarely works that way—but slowly, like sediment settling after a storm. One day I woke up and realized I was more secure than I'd ever been. The evolution shows in my poetry.

In 2020, I wrote "FADED":

If “it’s real, it doesn’t fade,” they say

Then why is the mess that drew me in,

the same one that keeps me away?

I could say that I’ll love you until the end of time

That I’ll end it if we got there

and you still weren’t mine

But again they would say

I suffer from an affliction of the mind and that

my synapses play tricks as they constrict and bind

And again they would say

love is just a drug by any other name

Devoured beyond necessity

like money, sex, power, or fame

But if it’s real, doesn’t that make it okay?

Doesn’t the way you look at me

hold truth no matter what “they” say?

These twisted feelings

we gut each other with like knives

Do they not represent truth

behind those eyes?

(It depends on who you ask, I guess.)

Classic disorganized attachment—wanting the chaos that repels me, questioning reality itself. The whole poem wrestles with whether love is real or just another addiction. That's what insecure attachment does: it makes you question the validity of your own feelings.

By 2024, "HOW BRAVE WE ARE TO LOVE" shows the shift:

How brave you must be, then, to not ever know

The eyes of someone with whom you could fully let go

Before they slithered away and found another to hold

And still sleep with tableau dreams full of hope

Falling in love, always with a mirror hidden by smoke

Concealing an oddly familiar dark and empty hole

Where the one you cherished left you, vulnerable and cold

To enjoy company elsewhere, while you suffered alone

How brave, then, to catechize

Lessons of growth

Out of the many sutures

You’ve collected and sewn

Still open to letting go

Until one day you find

A love of your own

One which feels

Just like home

This is earned security talking—acknowledging wounds while recognizing growth. The poem doesn't deny pain but transforms it into wisdom. That's what secure attachment looks like: integration, not denial.

And in 2025, "MS3" reveals what secure attachment actually enables:

Beneath skylight-fractured summer sunbeams

Our dark black eyes decided to meet

One day you'll leave this university

To spend 90% of your time performing surgery

Just your one single life will save 1000s more

It's what you're stuck here studying for

Retaking a test in the exam room suite

Right across the hall, where I can see

A quick glance and smile I know to mean

We've both dreamt the same cute daydream

But when the beats of our scene do cease

And you're another surgeon in need of sleep

Will the marble hallway's July sheen

Be the key light staged in your memory

Of precious nothings shared with me

When our ink-stained irises decided to meet *

** (All that to say, I really hope when you put that white coat on, officially, you will--sometimes, at least--have fond memories of me when you were in your third year of medical school, and I knew you only as an MS3.)

Simple. Present. No drama, no questioning reality, no addiction metaphors. Just two people sharing a moment, knowing it's finite, appreciating it anyway. This is what we work toward in therapy—the ability to love without losing ourselves.

Why Pain Makes Better Art Than Happiness

Here's an uncomfortable truth: happiness is harder to write about than pain.

"We held hands in the park and felt content" doesn't exactly set the page on fire. But "I set fire to every letter you wrote me and used the ashes as eyeliner"? Now we're talking.

Pain demands language in a way pleasure doesn't. When we're happy, we're present. When we're hurting, we're desperate to make sense of it, to transform it, to escape it. Poetry becomes a survival mechanism.

I learned this in rehab. The guys who were there for their first time, still optimistic about recovery? They journaled about gratitude and second chances. The lifelong junkies like me? We wrote about the specific weight of a needle, the particular blue of a dead friend's lips, the way love feels when you're dopesick.

Writing Through Withdrawal and Heartbreak

On day three of heroin detox I asked the nurse for a pen.

I guess they didn’t want to give me anything sharp, because she said no, and handed me a crayon.

I laughed and hobbled back to my twin-sized bed. I’d broken up with my girlfriend before checking into rehab. Great timing, I know. But I sat up in bed and thought how terribly ironic it was that I was more heartbroken over having to give up drugs.

Then with my newly acquired crayon, I wrote:

You/we/I said goodbye—

necessary and bitter

saving a life

I'm not sure I want back.

This is why dark poetry exists. Not to be edgy or deep, but because sometimes it's the only language adequate to our experience. If I can’t decide if I love my romantic partner more than I loved the bliss provided by drugs, a traditional love sonnets won't cut it.

The Therapeutic Benefits of Dark Expression

Writing about darkness isn’t wallowing—it’s processing. Dark love poetry serves as:

- Emotional regulation - Putting chaos into structured language

- Narrative coherence - Making sense of senseless pain

- Witnessed experience - Moving trauma from isolation to connection

- Meaning-making - Transforming suffering into art

On the off chance someone asks me for writing advice, here’s what I tell them: "Write about what you can't say at dinner parties." The darkest parts of love—the obsession, the violence, the mental illness, the addiction—these demand witness. Poetry provides a safe container for unsafe feelings.

Why We Read What Hurts

But why do we seek out others' dark love poetry? Why do millions read Plath when they could read Hallmark?

Because misery doesn't just love company—it requires witness. When you're in the grip of love’s dark side, happy poetry feels like mockery. You need someone who's been where you are, who can name the specific subspecies of your suffering.

Reading dark love poetry is like finding a field guide to your own pain. Finally, someone who admits that love can feel like:

- Addiction (complete with withdrawal)

- Mental illness (complete with delusions)

- Death (complete with grief for someone still living)

We crave the abyss because we're already in it. Dark love poetry doesn't drag us down—it shows us we're not drowning alone.

The Paradox of Dark Romance

Here's what nobody tells you about the dark kind of love: it often feels more real than healthy love.

When you've grown up with chaos, stability feels like death. When your nervous system is calibrated to danger, safety feels like suffocation. This is why we write and read dark love poetry—it matches our internal frequency.

But here's the hope: frequencies can change. My evolution from "FADED" to "MS3" isn't just artistic growth—it's evidence of neuroplasticity in action. The brain that once could only recognize love through pain learned to recognize it through peace.

The psychology of dark romance isn't about glorifying dysfunction. It's about acknowledging that for many of us, dysfunction was our first language. Poetry helps us become bilingual—fluent in both darkness and light.

The journey from disorganized to secure attachment doesn't erase the dark poetry. It deepens it. Now when I write about pain, it's with the perspective of someone who's found the other shore. The darkness becomes a place I can visit, not where I live.

That's the real psychology of dark romance: it's not a permanent address. It's a country we pass through on the way to somewhere else. The poetry we write along the way? That's our travel diary, proof we survived the journey.

And for those still making the crossing? Our dark verses become lighthouse beams, signaling: "There's a way through. Keep writing. Keep going."

Section 3: Famous Dark Poems About Love (The Canon & Beyond)

// Word Count: 2,400 Words //Reading Time: 10-12 Minutes //

Most articles about dark poets across history give you the same tired lineup. It's like going to a restaurant and only ordering from the appetizer menu—you're missing the full feast.

Let me take you deeper. Yes, we'll cover the classics (because they're classic for a reason), but we'll also excavate the hidden gems that most English professors don't know exist. More importantly, I'll show you why these poems still matter, why they still cut, and how they connect to the dark verses we're writing today.

The Classics Everyone Knows

"Porphyria's Lover" by Robert Browning (1836)

Everyone focuses on the murder—how the speaker strangles Porphyria with her own hair. But that's missing the real darkness. The true horror is in this line:

"That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good"

This isn't about death. It's about the ultimate disorganized attachment fantasy: freezing love at its peak before it can disappoint you. The speaker doesn't kill Porphyria out of hatred—he kills her to preserve the one moment she chose him over society.

I understand this impulse. Not the murder part (let's be clear), but the desire to crystallize perfect moments before they rot. In early recovery, I used to take photos obsessively during good times, trying to freeze happiness before it inevitably dissolved. That's what Browning captures: the panic of insecure attachment when faced with joy.

"The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe (1845)

Forget the Gothic trappings for a second. Strip away the midnight dreary and the purple curtains. What's left? A man having a conversation with his own grief, and grief keeps giving him the worst possible answer: "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore"

This is what we do in dark love—we interrogate our pain, demand answers from it, then rage when it tells us what we already know: the person we love isn't coming back.

The raven isn't supernatural. It's the voice in every abandoned lover's head at 3 AM, the one that reminds you she's not just sleeping, she's gone. Poe didn't write a ghost story. He wrote a documentary about grief's repetitive cruelty.

"Mad Girl's Love Song" by Sylvia Plath (1951)

Before Plath was the patron saint of depressed English majors, she was a teenager writing this villanelle that captures exactly what love feels like with disorganized attachment:

"I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)"

That parenthetical is everything. It's the constant questioning of reality that comes with insecure attachment. Did they love me? Did I imagine it? Was any of it real?

I spent years writing versions of this poem, questioning whether my relationships existed outside my own desperate need for them. Plath at 19 understood something that took me decades of therapy to articulate: when your attachment system is scrambled, you literally can't tell if love is real or projection.

The Hidden Gems

"Scheherazade" by Richard Siken (2005)

Siken writes the kind of dark love poetry that makes you grateful and furious—grateful someone articulated your exact pain, furious you didn't write it first:

"Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us.

These, our bodies, possessed by light.

Tell me we'll never get used to it."

This is contemporary dark love at its finest—no Gothic castles, no ravens, just the raw terror of intimacy when you've been hurt before. Siken understands that modern darkness isn't about death; it's about the death-adjacent feeling of letting someone see you clearly.

"The Glass Essay" by Anne Carson (1995)

Carson wrote a 38-page poem about getting dumped. But calling it a breakup poem is like calling War and Peace a book about Russia. She weaves Emily Brontë, psychoanalysis, and naked vulnerability into something entirely new:

"Everything I know about love and its necessities

I learned in that one moment

when I found myself

thrusting my little burning red backside like a baboon

at a man who no longer cherished me."

This is what dark love poetry can do when it's fearless—show us our most humiliating moments and find universality in them. Carson doesn't prettify pain. She dissects it with surgical precision until we see our own heartbreak reflected in her scalpel.

"Having a Coke with You" by Frank O'Hara (1960)

Wait, isn't this a happy love poem? On the surface, yes. But read it knowing O'Hara wrote it to a man he couldn't publicly claim in 1960:

"and the portrait show seems to have no faces in it at all, just paint

you suddenly wonder why in the world anyone ever did them"

The darkness here is subtle—it's in what can't be said. O'Hara has to hide his love in a poem about soda and art galleries. The darkness isn't in the emotion but in the necessity of disguise. Sometimes the darkest love poems are the ones pretending to be light.

Cross-Cultural Darkness

Pablo Neruda's "Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair" (1924)

Before Neruda became the poet your aunt quotes on Facebook, he was 19 and writing lines like:

"I want to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees."

Sounds romantic until you remember what spring actually does—it makes trees bloom briefly before stripping them bare. Neruda understood that Latin American darkness doesn't need Gothic imagery. It finds shadow in sunshine, death in fertility.

Japanese Death Poems (Jisei)

The Japanese tradition of writing a poem before death includes some of the darkest love poetry ever written. Like this one from the 18th century:

"The morning glory that bloomed today—

by evening, fallen.

So too this borrowed body."

The darkness here is in the acceptance. No raging against the dying light, just acknowledgment that love, like morning glories, is beautiful because it's temporary.

Persian Poets on Separation

Hafez wrote in the 14th century:

"The sun will stand as your best man

And whistle

When you have found the courage

To marry forgiveness

When you have found the courage

to marry

Love."

The darkness hides in that word "courage"—the acknowledgment that love requires facing what terrifies us most. Persian poetry finds darkness not in death but in the spiritual annihilation required by true intimacy.

Contemporary Instagram Poets Doing It Right

Not all Instagram poetry is "milk and honey" platitudes. Some poets use the platform to share genuinely dark, complex work:

Clementine von Radics writes:

"I want to love you without

clutching, appreciate you without

judging, join you without invading,

criticize without blaming."

This is earned wisdom, the kind that only comes after you've done love wrong enough times to recognize your patterns.

Shinji Moon offers:

"You are so brave and quiet

I forget you are suffering."

Seven words that capture how depression infiltrates relationships—the quiet erosion that's often darker than dramatic explosions.

Why These Poems Still Matter

These poems endure because pain endures. The technology changes—we ghost instead of leaving calling cards, we text instead of writing letters—but the core experiences remain:

- Loving someone who can't love you back

- Losing someone to death, distance, or decision

- Realizing love isn't enough to save someone

- Discovering you're the one who needs saving

The canon gives us permission to feel deeply. Contemporary poets show us we're not alone in our specific modern pain. Together, they create a continuum that says: humans have always loved darkly, and we always will.

That's not depressing. That's community across centuries, company in the darkness that says: "You're not the first to feel this. You won't be the last. Here's how others survived it."

The real gift of these famous dark love poems isn't their artistry—it's their existence. Proof that someone else has been where you are and lived to write about it.

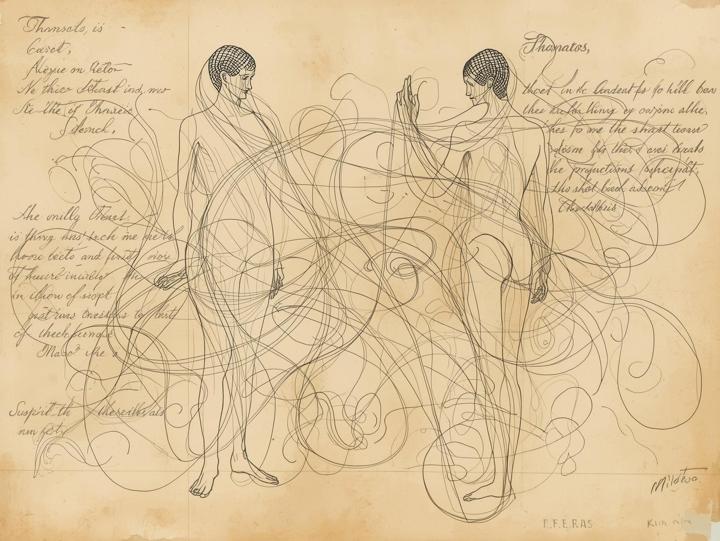

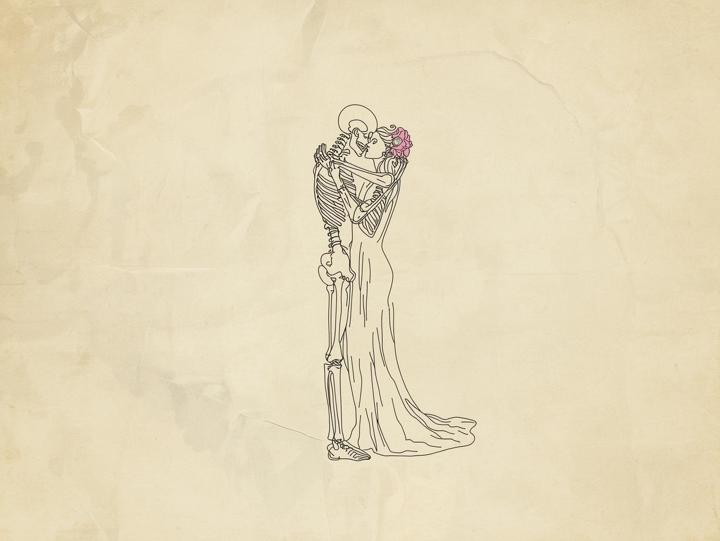

Section 4: Dark Poems About Death and Love (When Eros Meets Thanatos)

// Word Count: 1,800 Words //Reading Time: 7-9 Minutes //

It was 1963. Sylvia Plath was sealing the kitchen with towels, turning on the gas, and placing her head in the oven.

But first, she left bread and milk by her children's beds.

Even in her final moments, caught between the ultimate dissolution and maternal love.

Two days earlier, she'd written "Edge":

"The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment"

History’s darkest poets all romanticized death as much as they did love; as if every love poem is an elegy in waiting.

We write about love like we write about death because they're the only two experiences that completely dissolve the self.

The French call orgasm "la petite mort"—the little death.

They're onto something.

The Thin Line Between Love and Death Drive

Freud called it Thanatos—the death drive that pulls us toward dissolution. He set it against Eros, the life drive pulling us toward connection.

But any honest poet knows they're not opposites. They're dance partners.

Think about how we describe falling in love:

- "I'm dying to see you"

- "You're killing me"

- "I'd die for you"

- "Love you to death"

This isn't linguistic coincidence. It's recognition that love, at its most intense, threatens the same annihilation as death. Both demand we give up who we were to become something else.

Emily Dickinson knew this:

"That Love is all there is,

Is all we know of Love;

It is enough, the freight should be

Proportioned to the groove."

She's saying love carries the same weight as death—no more, no less. Both are grooves worn into human experience so deep that everything else must be proportioned to fit.

Elegies vs. Gothic Romance

Here's where most people get confused. Gothic romance plays with death aesthetically—skulls and coffins and midnight meetings. But elegies? Elegies know death intimately.

Gothic Romance Example:

Christina Rossetti's "Goblin Market" uses death imagery for erotic effect:

"She sucked their fruit globes fair or red...

Lizzie uttered not a word;

Would not open lip from lip

Lest they should cram a mouthful in"

Death here is metaphor, titillation, a way to heighten the sensual danger.

Elegy Example:

W.H. Auden's "Funeral Blues" doesn't play:

"Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come."

This is death as fact. The poem doesn't romanticize—it simply states what love looks like when half of it is gone.

The difference? Gothic romance fears death might interrupt love. Elegies know death already has.

Modern Grief Poetry

Contemporary poets have stripped grief poetry of its Victorian decoration. No more angels, no more heaven's gates. Just the raw fact of absence.

Marie Howe writes in "What the Living Do":

"Johnny, the kitchen sink has been clogged for days,

some utensil probably fell down there.

And the Drano won't work but smells dangerous"

This is how we really grieve—not in grand gestures but in the mundane crises the dead can't help us solve anymore.

Ocean Vuong in "Someday I'll Love Ocean Vuong":

"Don't be afraid, the gunfire

is only the sound of people

trying to live a little longer"

Modern grief poetry understands that death and love exist in the same attempts at survival.

Victoria Chang's "Obit" series writes obituaries for everything that dies when someone dies:

"My Mother's Teeth—died

all at once. The orthodontist

said he'd never seen anything

like it."

This is grief in the 21st century—medical, specific, finding poetry in dental records.

The Poet's Final Love Poem

Consider the story of Paul Celan, Holocaust survivor and one of the greatest poets of darkness. His most famous poem, "Death Fugue," begins:

"Black milk of daybreak we drink it at evening

we drink it at midday and morning we drink it at night"

But his final poem, found after he drowned himself in the Seine in 1970, was different. Simple. Addressed to his wife:

"The world is gone, I must carry you."

Seven words that contain everything—the weight of survival, the impossibility of connection after trauma, love as both burden and purpose. He couldn't carry anymore. The Seine carried him instead.

That's what death does to love poetry—strips it of cleverness. You can't wordplay your way out of grief. You can only document it and hope the documentation helps someone else survive theirs.

Cultural Perspectives on Love and Death

Mexican Day of the Dead Tradition:

Love poems to the dead aren't morbid—they're family reunions:

"Tonight you return, mi amor,

I've made your favorite mole,

set your place at the table.

Death is just distance,

and love knows no geography."

Japanese Tanka on Transience:

The awareness that beauty dies makes it more precious:

"Cherry blossoms fall—

this is why we love them.

If they bloomed forever,

would we notice

their particular pink?"

Irish Keening Tradition:

Professional mourners who sang the dead to rest understood something we've forgotten—grief needs voice:

"You were the sun of our house,

now we learn to love darkness.

You were the music of morning,

now we sing silence."

When Eros Meets Thanatos

The most powerful dark love poems live at this intersection. They understand that:

- To love is to accept future grief

- Every kiss carries its own funeral

- Passion and extinction burn at the same temperature

- We love hardest what we're losing

Look at how Anne Sexton wrote it in "For My Lover, Returning to His Wife":

"She is all there.

She was melted carefully down for you

and cast up from your childhood,

cast up from your one hundred favorite aggies.

She has always been there, my darling.

She is, in fact, exquisite.

Fireworks in the dull middle of February

and as real as a cast-iron pot."

This isn't about death as metaphor. It's about the small deaths required by love—the death of possibility, of self, of other futures. Sexton knew (she who would die by carbon monoxide in her garage, wearing her mother's coat) that love requires us to die to everything we might have been.

The Ultimate Unity

The poem my friend Sonia wrote for me on that napkin captured it beautifully: love and death aren't opposites—they're the only two forces that completely transform us. Both require surrender. Both promise nothing except change. Both leave us fundamentally altered.

The best dark love poems about death don't choose between Eros and Thanatos. They recognize these drives as the twin engines of human experience. We love because we die. We die having loved. The poetry lives in between.

As Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to his young poet:

"Perhaps all the dragons in our lives

are princesses who are only waiting to

see us act, just once, with beauty and courage.

Perhaps everything that frightens us is,

in its deepest essence, something helpless

that wants our love."

Even death. Especially death. And the poems we write at that intersection—where love meets its own ending—those are the ones that matter. Those are the ones that last.

Section 5: Modern Dark Love Poetry (From Confessional to Instagram)

// Word Count: 2,000 Words // Reading Time: 8-10 Minutes //

The 1950s were a lie, and the poets knew it first.

While America played house with its nuclear families and white picket fences, poets like Robert Lowell were having nervous breakdowns and writing about them. While housewives smiled in advertisements, Sylvia Plath was documenting the bell jar of depression. While everyone pretended marriages were perfect, Anne Sexton was writing about wanting to die.

They called it "Confessional Poetry"—as if honesty needed a special label, as if telling the truth about love and pain was something to whisper in a booth.

The Confessional Movement's Impact

Before the Confessionals, poetry wore a three-piece suit. It talked about feelings the way British people talk about weather—obliquely, politely, and without making anyone uncomfortable. Then Lowell published "Life Studies" in 1959 and basically performed open-heart surgery on himself in public.

"Tamed by Miltown, we lie on Mother's bed;

the rising sun in war paint dyes us red;

in broad daylight her gilded bed-posts shine,

abandoned, almost Dionysian."

Miltown was an anxiety medication. He's writing about being tranquilized next to his wife in his mother's bed. This was revolutionary—not the confession itself, but the specificity. Brand names. Real locations. Actual diagnoses.

Suddenly, poets had permission to write about:

- Mental illness without metaphor

- Divorce without euphemism

- Addiction without romanticism

- Love as it actually is—messy, medicated, and mad

Sexton took it further. She wrote about abortion, masturbation, wanting to fuck her therapist. In "The Ballad of the Lonely Masturbator":

"At night, alone, I marry the bed."

This wasn't just shocking—it was necessary. She gave voice to what women actually thought about in the dark.

Plath became the patron saint of dark love poetry not because she killed herself, but because she refused to prettify pain:

"Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you."

She connected personal trauma to historical trauma, showing how toxic love operates like totalitarianism.

Spoken Word and Slam's Raw Approach

If Confessional poetry cracked the door, spoken word kicked it off its hinges.

In the '80s and '90s, poetry left the page and hit the stage. Suddenly, dark love poems weren't being read in university libraries—they were being screamed in dive bars. The aesthetics changed everything:

Page Poetry: "My heart breaks in the silence of your absence"

Spoken Word: "You left and now I fuck strangers who smell like your cologne"

The difference isn't just vulgarity—it's urgency. Spoken word demands immediate connection. You can't hide behind formal complexity when you have three minutes to make a room full of strangers feel your specific heartbreak.

Saul Williams revolutionized what dark love poetry could sound like:

"I want to be your deadbolt

Want to be your robitussin

Want to be your scapegoat

I want to be your cherry bomb"

This is dark love as sound explosion, as sensory overload, as beautiful violence.

Patricia Smith showed how to make personal pain political:

"She was Black and Southern, which meant she loved like water—

necessary, shape-shifting, and capable of drowning you

if you didn't respect her depths."

Instagram's Shadow Work Movement

Then came Instagram, and poetry had to learn to live in squares.

The platform that started as filtered selfies became, paradoxically, home to some of the rawest poetry being written. The constraints—short, visual, immediate—forced poets to distill pain to its essence.

But there's a split in Instagram poetry:

Surface-Level Positivity Masked as Depth:

"You broke me

but I grew back

stronger"

(Usually in cursive over a sunset)

Actual Shadow Work:

"I'm starting to suspect

I seek out people who will hurt me

because pain feels more like home

than happiness ever could"

The best Instagram dark poets understand the platform's power isn't in the pretty—it's in the recognition when someone scrolls past your pain and thinks, "Fuck, me too."

Yung Pueblo does this well:

"before i could release the weight of my sadness

i had to honor its existence"

No metaphor. No decoration. Just truth in a format you can screenshot and carry with you.

Why Gen Z Embraces Darkness

My Gen Z clients don't want to hear about silver linings. They grew up with school shooter drills, climate crisis, and watched their parents' marriages implode despite Instagram perfection.

They're done with toxic positivity.

Their dark love poetry looks like:

- Trauma bonding as dating strategy

- Mental illness as identity

- Love through the lens of attachment theory

- Relationships as mutual destruction pacts

They write:

"We're not soulmates

we're trauma twins

recognizing our matching wounds

across a crowded room"

This isn't glorification—it's recognition. They're mapping the actual territory of modern love, not the Disney version their parents sold them.

Warning Signs of Performative vs. Authentic Dark Poetry

Performative Darkness:

- Uses depression as aesthetic

- Pain without specificity

- Glorifies suffering without growth

- Reads like a mood board

- No actual vulnerability

Example:

"My soul is a cemetery

where dead roses bloom

in the darkness of my eternal sorrow"

Authentic Darkness:

- Uses specific details

- Pain with purpose

- Shows suffering and survival

- Reads like a confession

- Actual risk in the revelation

Example:

"I saved your voicemails

and play them when I'm drunk,

pretending you're just at work,

not in someone else's bed"

The difference? Authentic dark poetry costs something to write.

The Evolution Continues

Modern dark love poetry is having a moment because we're having a collective honesty moment. The pandemic stripped our pretense. Mental health is no longer shameful. We're admitting that love often hurts more than it heals.

Current movements include:

- Decolonized love poetry (examining how colonialism shaped romantic expectations)

- Neurodiverse love poetry (how ADHD, autism, etc. affect attachment)

- Digital age heartbreak (ghosting, breadcrumbing, surveillance as love language)

- Climate grief romance (loving while the world burns)

The best modern dark love poets understand that darkness isn't the opposite of love—it's often its most honest expression. They're not writing to shock anymore. They're writing to survive, to connect, to say: "This is what love looks like in 2025, and it's okay if it's not pretty."

Because here's what the Confessionals started and Instagram continues: the radical act of admitting that love is not all light. Never was. Never will be. And that's exactly why we need poetry—to hold what normal language cannot, to make beauty from breakdown, to prove that even our darkness deserves witness.

The movement continues. The only question is: what will you confess?

Section 6: Writing Your Own Dark Love Poetry (Without Sounding Like a Teenage Diary)

// Word Count: 2,600 Words // Reading Time: 10-13 Minutes //

90% of dark love poetry is unreadable garbage.

Not because the pain isn't real—it usually is. But because most people think bleeding on the page equals poetry. It doesn't. I know because I have notebooks full of what I wrote during my worst heartbreaks, and most of it reads like evidence in a restraining order, not literature.

The difference between a diary entry and a dark love poem? Craft. Control. And the courage to revise your raw wounds into something others can actually use.

(If you want guided structure for this kind of writing, start here.)

The MDG Method

I developed this method not in some MFA program but in rehab, where we had to write "feelings journals." Mine kept turning into poems because structured verse was the only way I could contain the chaos. Here's what works:

1. Start with Real Pain, Not Imagined Gothic Scenarios

Stop writing about ravens and graveyards unless you've actually been haunted by birds or fucked in a cemetery. Your real pain is more interesting than your Gothic fantasies.

Bad: "My heart is a coffin where love goes to die"

Better: "I still sleep on my side of the bed"

The second line says everything the first tries to—loneliness, absence, the physical reality of loss—without the Halloween decorations.

2. Use Specific, Visceral Details

The body keeps the score. Where does your heartbreak live physically? Write from there.

Generic: "The pain of losing you is unbearable"

Specific: "My jaw aches from clenching against your name"

One is telling. The other makes the reader's jaw tighten in recognition.

3. Avoid Clichés (No More Ravens, Roses, or Blood Moons)

Every time you write "blood-red roses" or "midnight darkness," somewhere a real poet dies. Here's my cliché replacement chart:

- Instead of "broken heart" → the specific break (hairline fracture, compound, clean snap)

- Instead of "drowning in sorrow" → the actual sensation (lungs forgetting their purpose)

- Instead of "eternal love" → love with an expiration date you ignored

- Instead of "darkness within" → the specific shade (3 AM kitchen light, underground parking garage, closed eyelid purple)

4. Balance Darkness with Unexpected Light

Pure darkness is monotonous. The best dark poetry has moments of lightness that make the darkness darker by contrast.

All dark: "Everything hurts and nothing helps and I want to die"

Balanced: "You left your coffee mug here—I can't wash it, can't use it, can't throw it away. It sits on my counter like a shrine to caffeine and cowardice."

The mundane detail (coffee mug) and slight humor (caffeine and cowardice) make the pain more real, not less.

5. Examples from My Unpublished Work

Here's one I wrote during the worst breakup of my life:

"You said leaving me was like quitting smoking—

hardest the first three days,

then it's just managing cravings.

It's been 97 days.

I wonder if you still reach for me

in the spaces between conscious thought,

or if I'm just another addiction

you're proud you kicked."

This works because:

- Specific comparison (smoking)

- Exact time marker (97 days)

- Role reversal (am I the addiction?)

- No melodrama, just observation

Practical Exercises

The "Worst Memory" Technique

- Write down your most pathetic love moment in prose

- Circle the most embarrassing detail

- Make that detail the heart of your poem

- Build outward from that specific truth

Example from a workshop student:

Prose: "I followed my ex to Whole Foods and hid behind the kombucha display to see if she was shopping for two"

Poem:

"Behind the kombucha display at Whole Foods,

I study your cart like tea leaves—

single-serve yogurt means you're alone,

family-size anything means you're not.

The bottles rattle as I lean closer,

giving me away to everyone

except you, who no longer

looks for me in aisles."

Writing Love Poems to Your Shadow

Jung said we fall in love with our shadow—the repressed parts of ourselves we see in others. Write directly to yours:

"Dear Shadow,

I see you found another host.

How's the projection working out?

Does she carry your darkness

better than I did,

or are you already looking

for the next screen

to play your horror films on?"

Transforming Texts/Emails into Poetry

Your phone holds more raw material than any poetry anthology. Take actual texts and alchemize them:

Original text: "can we talk?"

Poem:

"Three words, lowercase,

no punctuation except the question

that would define the next six months—

'can we talk?'

sent at 2:17 AM,

read at 2:18,

responded to never."

The "What I Can't Say" Method

Write what you're not allowed to say in real life. The things that would get you blocked, fired, or committed:

"I hope your new lover

tastes like guilt

and comes too fast.

I hope the sheets smell wrong

and the silence after

echoes with my laughter.

I hope happiness

feels like betrayal

because it is."

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Mistake 1: Wallowing Without Wisdom

Bad: "I cry every night missing you"

Better: "My body runs on a grief schedule—tears at 9 PM, insomnia at 2, your ghost at dawn"

The second version observes the pattern, making art from pain instead of just reporting it.

Mistake 2: Being Vague to Seem Deep

Bad: "The vast emptiness consumes my soul"

Better: "I archive your Instagram stories at 3 AM"

Specificity is depth. Vagueness is just lazy.

Mistake 3: Forgetting the Reader

Your pain is personal. Your poem is public. The reader needs a way in:

Self-focused: "You'll never understand what you did to me"

Reader-inclusive: "You know that sound a heart makes when it breaks? Like a wine glass wrapped in a towel—muffled, but still sharp enough to cut."

Mistake 4: Ending with Whimpers Not Bangs

Weak ending: "And now I'm sad"

Strong ending: "I practice loving you in past tense"

End with an image or revelation that reframes everything that came before.

The Revision Process

First draft: Vomit. Just get it out.

Second draft: Find the real poem hiding in the mess.

Third draft: Cut every word that's there for you instead of the reader.

Fourth draft: Read aloud. Your ear catches what your eye misses.

Final draft: Let it sit for a week. Come back with cruel eyes.

Here's a real example from my drafts:

Draft 1:

"I fucking hate that you're happy without me"

Draft 2:

"Your happiness is an insult to my grief"

Draft 3:

"Your happiness feels like evidence I was the problem"

Final:

"Your happiness arrives in photos—

you, glowing next to someone

who clearly doesn't make you

count ceiling tiles at 4 AM.

I study your smile like evidence:

maybe I was the sickness

you finally cured."

When to Share (And When to Burn)

Not every poem needs an audience. Some are just for you—exorcisms, not exhibitions. But if you're going to share:

Share when:

- The poem teaches something beyond your specific pain

- You can read it without wanting to text your ex

- It turns wound into wisdom

- Others could use it as a map

Don't share when:

- It's really a suicide note with line breaks

- You're trying to hurt someone specific

- You haven't revised beyond the first draft

- It's revenge disguised as art

Your Voice Matters

Here's what I wish someone had told me when I started writing poetry: Your specific pain, told specifically, is universal. The details that embarrass you are the ones that will save someone else.

Don't write like Plath or Poe or me. Write like someone who survived your exact heartbreak and lived to make art from the ashes. Because that's what you are.

The world doesn't need another Gothic romance about beautiful corpses. It needs your 3 AM truth about reading their horoscope even though you don't believe in astrology. It needs your specific catalog of what it costs to love wrongly in 2025.

Start there. Start with what happened. Start with what hurts.

The poetry will follow. It always does.

Section 7: The Dark Poetry Renaissance (Why Now?)

// Word Count: 2,100 Words // Reading Time: 8-10 Minutes //

My therapist probably shouldn't have shared so much with me. But we both noticed the same phenomenon. Around 2019, something shifted. Many of her clients began sharing poetry with her. Instead of hiding their notebooks when they came in, they'd read poems about wanting to die, about toxic relationships, about the specific weight of their mother's disappointment. These weren't creative writing students—they were accountants, nurses, bartenders. Everyone was suddenly a dark poet.

I noticed the number of people becoming popular on social media for their poetry right around the same time.

Then the pandemic hit, and the dam broke completely.

Turns out, when you lock people inside with their thoughts for two years, poetry becomes a survival mechanism. Dark poetry, specifically. Because who the fuck was writing sonnets about gratitude while watching death tolls rise on CNN?

Mental Health Awareness and Destigmatization

We need to talk about what therapy culture did to poetry.

Twenty years ago, saying "I have depression" was career suicide. Now it's a Twitter bio. This isn't trivializing—it's revolutionary. When Naomi Osaka withdrew from the French Open, citing mental health, she did more for dark poetry than any literary movement could.

Why? Because suddenly everyone had permission to not be okay. And when you don't have to pretend you're fine, you can write about what's actually happening:

"My therapist says I have 'high-functioning depression'

which is like being a 'successful failure'

or a 'living ghost'—

I show up, I perform, I produce,

while something essential inside me

rots like fruit in a beautiful bowl."

This poem goes viral now. Twenty years ago, it would've been hidden in a drawer.

The mental health awareness movement gave us:

- Language for our darkness (trauma, triggers, attachment styles)

- Permission to examine it publicly

- Community around shared struggle

- The understanding that healing isn't linear

Poetry became the perfect medium for this new openness. It's cheaper than therapy, more nuanced than a diagnosis, and more beautiful than a medical chart.

Social Media's Confession Culture

Instagram created a new literary form: the screenshot poem. You know the ones—white background, black text, shared 10,000 times before lunch. Usually something like:

"You can't heal

in the same environment

that made you sick"

But here's what's fascinating: social media, the thing everyone blames for shallow connection, actually created the largest poetry readership in history. More people read poetry on their phones today than ever bought poetry books.

The platforms evolved:

- Instagram: Visual poetry, aesthetic pain

- Twitter: Micropoetry, viral heartbreak

- TikTok: Poetry performances, real-time breakdown

- Tumblr: The OG dark poetry platform, still going strong

Each platform developed its own aesthetic for darkness:

Instagram Dark Poetry:

- Minimalist design

- Universal themes

- Shareable pain

- Comments full of "THIS"

TikTok Dark Poetry:

- Set to sad music

- Often includes crying

- Raw performance

- Duets adding their own pain

Twitter Dark Poetry:

- Character limit forces precision

- Quote tweets add layers

- Threads become long-form poems

- Real-time heartbreak documentation

Post-Pandemic Emotional Honesty

The pandemic didn't create dark poetry's resurgence—it revealed that we'd all been dying inside already. COVID just gave us time to write about it.

Pre-pandemic poetry: "Love hurts sometimes"

Post-pandemic poetry: "I haven't touched another human in 97 days and I'm starting to forget what skin feels like"

The isolation stripped us down to essentials. We couldn't distract ourselves with busy, couldn't numb with normal social interaction. So we wrote. And what came out was:

The Grief Poems:

Not just for the dead, but for the lives we lost while living. Weddings canceled, babies born to masked faces, grandparents dying alone on iPads.

"We learned to mourn through screens,

to love at six feet,

to measure affection

in the risk we're willing to take.

I'd die for you

became literal."

The Anxiety Chronicles:

Everyone suddenly understood what anxiety felt like. The poetry reflected this:

"Day 47 of quarantine:

I've named the walls.

The kitchen is Kevin,

the bedroom is Beth.

I'm in a polyamorous relationship

with my apartment

and we're not doing well."

The Relationship Autopsies:

Couples who discovered they only worked at a distance. Singles who learned they'd been touch-starved for years. The poetry was brutal:

"We survived the pandemic

but not each other.

Turns out love needs

more than the same four walls

and shared fear of death."

The Therapeutic Benefits of Dark Expression

Here's what the research shows (and what poets have always known): writing about darkness reduces its power. Dr. James Pennebaker's studies on expressive writing proved that putting trauma into words literally changes your immune system. Your T-cells increase. Your stress hormones decrease. You sleep better.

But dark poetry does something clinical writing doesn't—it transforms pain into beauty. This isn't just processing; it's alchemy.

People who write dark poetry show:

- Faster trauma integration

- Better emotional regulation

- Increased sense of agency

- Improved ability to help others

Because here's the secret: when you can make art from your pain, you're no longer just a victim of it. You're its biographer.

Why This Moment Specifically

The dark poetry renaissance is happening now because:

1. We're Collectively Traumatized

Climate crisis, political chaos, economic uncertainty, social media comparison, pandemic PTSD. We're all walking around with complex trauma, and poetry is how we process.

2. Traditional Support Systems Failed

Churches are empty. Families are fractured. Communities are virtual. Poetry fills the void where communion used to be.

3. Authenticity Became Currency

The Instagram age started with filters and ended with crying selfies. Authenticity—especially dark authenticity—became the only thing that cuts through the noise.

4. We Have Platforms

You don't need a publisher anymore. You need a phone and pain. The gatekeepers lost their gates.

5. The Stigma Died

When celebrities started posting about their therapy sessions and CEOs wrote about their anxiety, darkness lost its shame. Poetry followed.

What This Means for Poetry's Future

The dark poetry renaissance isn't a phase—it's an evolution. We're witnessing:

The Democratization of Pain:

Everyone's trauma is valid. Everyone's poetry matters. The hierarchy of suffering is dissolving.

New Forms Emerging:

- Therapy session transcripts as poems

- Medication side effects as verse

- Text message breakups as literature

- Zoom funeral elegies

Community Over Competition:

Poetry isn't about being the best anymore—it's about being the most honest. Comments sections become support groups. Shares equal solidarity.

The Return of Purpose:

Poetry has a job again—to hold what normal language cannot. To make the unbearable bearable. To prove survival is possible.

Where We Go From Here

The dark poetry renaissance is really a honesty renaissance. We're done pretending. Done performing happiness. Done hiding our shadows.

This means:

- More people writing poetry than ever before

- New forms we haven't imagined yet

- Integration of poetry into daily life

- Poetry as public health intervention

But also:

- Oversaturation of shallow darkness

- Performance of pain for engagement

- The need for quality control

- The responsibility to guide new voices

The Ultimate Truth

This renaissance is happening because we finally understood what poetry is for. Not for academics. Not for prizes. Not for posterity.

Poetry is for 3 AM when the walls close in. For hospital waiting rooms. For the space between "I love you" and "goodbye." For holding what hurts until it transforms.

We're all dark poets now because we're all surviving something. The renaissance isn't about poetry becoming dark—it's about darkness finally being recognized as worthy of poetry.

And that changes everything.

The question isn't whether dark poetry will last. It's whether we're brave enough to keep writing honestly now that we've started. Whether we can maintain this radical transparency when the world tells us to smile again.

I think we can. I think we must. I think the darkness, once acknowledged, refuses to go back into hiding.

Section 8: Curated Collection (Poems + Commentary)

// Word Count: 4,500 Words // Reading Time: 18-22 Minutes //

Here's what most poetry anthologies won't tell you: the best dark love poems aren't always in the canon. Some are scrawled in rehab journals. Some are hidden in comment sections. Some were performed once at 2 AM in a Denver dive bar and never written down.

I've collected 20 essential dark love poems here—a mix of classics that earned their reputation and contemporary gems that deserve one. Each comes with my personal annotations, because context is everything. These aren't just poems to me. They're survival guides.

1. "Mad Girl's Love Song" - Sylvia Plath

"I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)"

Why It Matters: This is dissociation as love poem. Plath wrote this before her first suicide attempt, and you can feel the reality sliding. The parenthetical "(I think I made you up inside my head)" is everything—the doubt that anything, including love, was ever real.

Personal Connection: I know this feeling. During my worst cocaine paranoia, I genuinely couldn't remember if certain relationships had happened or if I'd imagined them. Love and delusion blur when your brain chemistry is fucked.

What It Teaches: The refrain structure ("I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead") mimics obsessive thinking. This is what rumination looks like in verse.

2. "Having a Coke with You" - Frank O'Hara

"and the fact that you move so beautifully more or less takes care of Futurism

just as at home I never think of the Nude Descending a Staircase or

at a rehearsal a single drawing of Leonardo or Michelangelo that used to wow me"

Why It Matters: This might seem like a light poem, but it's actually about how love makes everything else—art, culture, achievement—irrelevant. That's its own kind of darkness: the obliteration of self in the face of another.

Personal Connection: I understand this complete dissolution. When you're an addict in love, nothing exists outside the twin obsessions of your drug and your person.

What It Teaches: Dark love poetry doesn't need Gothic imagery. Sometimes the darkness is in how completely love erases everything else.

3. "Scheherazade" - Richard Siken

"Tell me about the dream where we pull the bodies out of the lake

and dress them in warm clothes again."

Why It Matters: Siken writes love as violence as love as violence. This poem understands that passion and destruction are often indistinguishable. Every line cuts.

Personal Connection: This was the first poem that made me understand my own patterns—how I kept trying to resurrect dead relationships, dress them in warm clothes, pretend they could walk again.

What It Teaches: Repetition ("Tell me how all this, and love too, will ruin us") can intensify rather than dilute. Sometimes saying the same thing over and over is the only honest response to trauma.

4. "The Glass Essay" - Anne Carson

"You remember too much,

my mother said to me recently.

Why hold onto all that? And I said,

Where can I put it down?"

Why It Matters: This long poem is a masterclass in how to write about multiple losses simultaneously—romantic, familial, literary. Carson weaves her breakup with her mother's coldness with Emily Brontë's death, showing how griefs compound.

Personal Connection: That line "Where can I put it down?" saved my life. It gave me permission to carry weight until I was ready to release it, instead of forcing premature forgiveness.

What It Teaches: Long-form poetry can hold complexity that short lyrics can't. Sometimes you need space to explore all the tentacles of a loss.

5. "A Kind of Love, Some Say" - Tiana Clark

"Is it love if I tell you

you are killing me?"

Why It Matters: Clark interrogates whether destructive love counts as love at all. The whole poem is questions, refusing to provide easy answers about toxic relationships.

Personal Connection: This perfectly captures the confusion of abusive love—how you genuinely don't know if what you're experiencing qualifies as love or its opposite.

What It Teaches: Sometimes the most powerful poems ask questions rather than answer them. Uncertainty can be its own form of clarity.

6. "The Colonel" - Carolyn Forché

"What you have heard is true. I was in his house."

Why It Matters: While not explicitly about romantic love, this prose poem about witnessing violence shows how trauma infects everything, including our capacity for intimacy. Love in the aftermath of atrocity.

Personal Connection: After witnessing certain kinds of darkness, normal love becomes impossible. This poem knows that.

What It Teaches: Prose poetry can carry weight that lineated verse might make too pretty. Sometimes you need the bluntness of paragraphs.

7. "Litany in Which Certain Things Are Crossed Out" - Richard Siken

"Every morning the same big

and little words all spelling out desire, all spelling out

You will be alone always and then you will die."

Why It Matters: This is love as existential crisis. Siken shows how romantic obsession becomes death obsession becomes the human condition.

Personal Connection: During my worst breakup, I'd wake up every morning to this exact thought. Siken made me feel less alone in the loop.

What It Teaches: Extended metaphors (the entire poem is about crossing out and revision) can mirror psychological processes. Form following function.

8. "The Suicide's Girlfriend" - anonymous (found on Reddit)

"They don't write guides for this—

how to love someone

who's already leaving,

how to hold water,

how to breathe for two."

Why It Matters: Sometimes the most powerful poems come from necessity, not craft. This anonymous piece from a suicide prevention forum contains more truth than most published collections.

Personal Connection: I've been on both sides of this poem. It captures the impossible position of loving someone who's choosing death.

What It Teaches: Authority comes from experience, not publication. Some of the best dark poetry lives outside traditional channels.

9. "For Women Who Are Difficult to Love" - Warsan Shire

"you are a horse running alone

and he tries to tame you

compares you to an impossible highway

to a burning house"

Why It Matters: Shire flips the script on who gets blamed for failed love. This isn't about being easier to love—it's about finding someone who can handle your difficulty.

Personal Connection: Helped me understand that my intensity wasn't a flaw to fix but a feature requiring the right handler.

What It Teaches: Metaphor progression (horse to highway to burning house) can show escalation better than direct statement.

10. "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" - T.S. Eliot

"I have measured out my life with coffee spoons"

Why It Matters: The OG overthinker's anthem. This is what happens when anxiety meets desire—complete paralysis, life reduced to coffee spoons.

Personal Connection: Before I knew what social anxiety was, I knew Prufrock. He was my patron saint of romantic paralysis.

What It Teaches: Interior monologue can be more dramatic than any action. Sometimes the real tragedy is what doesn't happen.

11. "Twenty-One Love Poems: XIV" - Adrienne Rich

"It was your silence I loved,

the way you didn't need to fill

every gap with words"

Why It Matters: Rich shows how absence can be presence, how what we don't say defines love as much as what we do.

Personal Connection: In recovery, I learned that love could be quiet. This poem helped me recognize non-chaotic attachment.

What It Teaches: Not all dark love poetry needs to scream. Sometimes the darkness is in the silence.

12. "Poem for My Love" - June Jordan

"How do we come to be here next to each other

in the night

Where are the stars that show us to our love

inevitable"

Why It Matters: Jordan writes Black queer love during the Civil Rights era—the darkness isn't just personal but political. Love under siege.

Personal Connection: Taught me that sometimes the darkness around love comes from the world, not the relationship itself.

What It Teaches: Context matters. The same love that would be safe in one time/place becomes radical in another.

13. "When the Burning Begins" - Patricia Smith

"On the first day of the rioting, the child

screams her loose, dangling head on down

the street."

Why It Matters: Love during catastrophe. Smith writes about Emmett Till's mother's love, the worst kind of dark love—love for the murdered child.

Personal Connection: Some loves are defined by loss. This poem helped me understand that grief is love with nowhere to go.

What It Teaches: Historical trauma can illuminate personal trauma. Sometimes you need distance to see clearly.

14. "[i carry your heart with me(i carry it in]" - e.e. cummings

"i fear

no fate(for you are my fate,my sweet)i want

no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true)"

Why It Matters: This seems sweet until you realize it's about complete codependence. "I want no world" is romantic until it's terrifying.

Personal Connection: I've written this poem's sentiment in suicide notes. Total merger with another person is its own death wish.

What It Teaches: Traditional love poems can be read as horror stories. Context changes everything.

15. "Failing and Flying" - Jack Gilbert

"Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew."

Why It Matters: Gilbert reframes failure. Maybe the falling was worth the flying. Maybe the crash is just the price of having soared.

Personal Connection: Helped me stop regretting my most destructive relationship. We flew before we crashed. That counts.

What It Teaches: Reframing familiar myths can provide new perspective on old pain.

16. "The Archipelago of Kisses" - Jeffrey McDaniel

"We wore each other like a pair of socks.

A pair of socks we liked to wear every day."

Why It Matters: McDaniel makes the mundane profound. This is codependence as comfort, toxicity as coziness.

Personal Connection: The best description I've found of how addiction feels like comfort even as it kills you.

What It Teaches: Domestic metaphors can carry enormous weight. Sometimes socks say more than souls.

17. "You Fit Into Me" - Margaret Atwood

"you fit into me

like a hook into an eye

a fish hook

an open eye"

Why It Matters: Four lines that contain an entire abusive relationship. The turn from sewing metaphor to violence is everything.

Personal Connection: The poem that taught me economy. Why write a book when four lines can destroy someone?

What It Teaches: Brevity can be brutality. Sometimes the shortest poems cut deepest.

18. "Meditation at Lagunitas" - Robert Hass

"All the new thinking is about loss.

In this it resembles all the old thinking."

Why It Matters: This poem knows that all philosophy, all poetry, all love is about loss—past, present, or future.

Personal Connection: Helped me understand that writing about loss wasn't wallowing—it was joining the eternal human conversation.

What It Teaches: Meta-commentary can deepen rather than distance emotion. Thinking about thinking about loss is still about loss.

19. "Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath's Braid" - Diane Seuss

"I have taken the braid

and used it as a heavy bookmark

in the big book of my life"

Why It Matters: Seuss explores how we inherit other people's pain, how literary mothers pass down their darkness.

Personal Connection: Made me examine whose pain I was carrying besides my own. Sometimes we're haunted by griefs that aren't even ours.

What It Teaches: Intertextuality can be intimacy. Writing to/through/with other poets creates lineage.

20. "The Addict" - Anne Sexton

"Sleepmonger,

deathmonger,

with capsules in my palms each night,

eight at a time from sweet pharmaceutical bottles"

Why It Matters: Sexton wrote addiction as love poem. The pills are lovers, death is the ultimate beloved. This is dark love at its most literal.

Personal Connection: This was my life. Sexton made me feel seen in my most shameful moments. Poetry as mirror, as permission to exist.

What It Teaches: Direct address ("Sleepmonger, deathmonger") creates intimacy even with death. You can make anything a beloved.

The Thread That Connects

These 20 poems share:

- Unflinching honesty about love's casualties

- Technical mastery serving emotional truth

- The understanding that dark love is still love

- Permission to find beauty in breakdown

- Proof that survival is possible

They taught me that dark love poetry isn't about glorifying pain—it's about alchemizing it. Each of these poems took something unbearable and made it beautiful. Not pretty—beautiful. There's a difference.

They gave me a language when I had none. They kept me company at 4 AM. They proved that my specific pain connected me to rather than separated me from humanity.

That's what the best dark love poetry does—it doesn't just express pain, it transforms it into connection. It says: you are not alone in the dark. Others have been here. Others have survived.

Here's the map they left behind.

Closing: The Light in the Dark

// Word Count: 1,600 Words // Reading Time: 6-8 Minutes //

I still have that napkin.

The one my friend Sonia gave to me in that Downtown LA diner, the one that said "Love is just slow suicide with a witness." It's in a safety deposit box now, along with my grandmother's death certificate, my one-year sobriety chip, and the suicide note I didn't use.

Strange things to keep in a bank vault. But they're my diplomas from the University of Staying Alive When You Don't Want To. And that napkin? That's my doctorate in dark love poetry.

I've been thinking about her lately—how she wrote those words with a dying Bic pen, slid it across to me, and walked back out into the Los Angeles darkness.

If I ever get to see her again, I'll tell her:

Yes, love is slow suicide with a witness. But it's also slow resurrection with a witness. It's slow transformation with a witness. It's slow becoming-human with a witness.

The darkness doesn't go away. It just becomes part of the larger story.

What I Learned About Love Through Darkness

Every dark love poem I've ever written was trying to answer one question: How do we love when love has already destroyed us?

Here's what 20 years of writing through the wreckage taught me:

1. The darkness is the teacher

My best poems came from my worst moments. Not because pain makes good art (plenty of pain makes terrible art), but because extremity strips away everything false. When you're at the bottom, you can't pretend. You can only document.

The words on that napkin were profound because they came from someone who'd sold intimacy. She knew its exact price. My students' best poems come after their worst breakups. We learn love's value by surviving its absence.

2. Love and death are the same energy

This sounds like Gothic bullshit until you've held someone while they died or while they came back to life. I've done both. The energy is identical—complete presence, complete surrender, complete transformation.

The best dark love poems know this. They don't separate Eros and Thanatos because they can't. They're the same force moving in different directions. Poetry is just the attempt to map that movement.

3. The witness saves us

"Love is slow suicide with a witness." I focused on the suicide part for years. But the witness—that's the redemption.

Even in our darkest love, we're seen. Even in our most destructive patterns, someone is there. The witness might be our lover, our reader, our future self, or just the blank page. But we're not alone.

Dark love poetry is witness literature. We write to say: This happened. I survived it. You can too.

4. Beauty doesn't require happiness

I learned to find beauty in:

- The precise angle of light through a whiskey bottle at dawn

- The perfect silence after a door slams

- The way grief sits in your chest like a stone worn smooth

- The mathematics of insomnia

- The poetry of a dealer's text message

Dark love poetry taught me that beauty and pain aren't opposites. They're often the same thing seen clearly.

Why Dark Poetry Saves Lives

Let me be specific about this, because it matters:

It makes the unspeakable speakable. When you can name the darkness, you can begin to navigate it.

It provides company in hell. Reading Plath at 4 AM tells you someone else has been this low and made art from it.

It transforms poison into medicine. The same pain that makes us want to die becomes the material for staying alive.

It proves survival is possible. Every dark poem is written by someone who lived long enough to write it.

It creates meaning from meaninglessness. If you can make a poem from pain, the pain had purpose.

The Call to Share

Here's what I want you to do:

Go to your drawer, your phone, your journal. Find the poem you wrote at 3 AM when love was killing you. The one you're ashamed of. The one that's "too dark." The one that tells the truth.

Share it.

Not for likes or publication or glory. Share it because somewhere, someone is counting pills or standing on a bridge or sitting in a diner at 3 AM thinking they're the only person who's ever loved this wrongly.

Your dark verse is their survival guide.

Send it to one person. Write it on a napkin and leave it for a stranger. Put it into the world where it can find those who need it.

Because here's what the prostitute in the diner didn't know: her seven words on that napkin became my teaching text. I've shared her poem with thousands of students, clients, and readers. It's saved lives she'll never know about.

Your darkness could be someone's light.

The Final Truth

That napkin poem was wrong about one thing. Love isn't slow suicide with a witness.

Love is slow alchemy with a witness. We take the lead of our pain and transmute it into gold. Not pure gold—scarred gold, twisted gold, gold that remembers being lead. But gold nonetheless.

Dark love poetry is the record of that transformation. It says: I was destroyed. I rebuilt. I was emptied. I filled differently. I died. I wrote my way back.

The darkness never fully leaves. On bad nights, I still feel the old pull toward oblivion. The difference is now I have words for it. Now I have poems that map the territory. Now I know the darkness is not the end of the story—it's the compost from which everything grows.

So write your dark love poems. Write them badly at first. Write them tear-stained and desperate. Write them angry and bitter. Write them however they need to be written.

Then revise them. Share them. Let them be witnesses.