This is the second essay in a series of three on The Evolution of Romantic Poetry.

- To read Part One: From The Classics to the Contemporary click here.

- To read Part Three: Craft, Technique, Form, & Innovations click here.

Introduction: How Poems About Love Shatter Cultural Barriers

My grandmother and I have never had a conversation with each other.

She was born in Mexico and speaks broken English. I was born in California and don’t speak Spanish so well. We've loved each other desperately for thirty years across a language barrier neither of us can cross.

She worked the kitchen of a cafe my dad used to own, and when I was given a summer job there as a kid, she made futile attempts to train me on food prep. Her weathered hands guided mine as she kneaded the masa dough for tamales, both of us silent except for her occasional laugh at my pathetic end products. Next to hers, mine looked like casualties of war.

But those kitchen moments contained more love within them than all the poetry I've ever written.

This is the paradox I've been wrestling with my whole career: how do you translate feelings that exist beyond language? How do you carry love across impossible distances—between languages, between cultures, between people who share DNA but can't share stories?

I used to think loving my grandmother despite our silence was unique to us. Then I started navigating through the poems about love in this world and realized something that knocked me sideways: every culture that's ever existed has faced this same impossible translation.

From Chinese monks condensing lifetimes into four-line poems to African griots singing love into memory before writing existed: we're all trying to capture what refuses capture.

Poetry isn't decoration. It's not some fancy way to say "I love you." It's desperation. It's what happens when the gap between what you feel and what you can say becomes unbearable. Every love poem ever written is a failed translation that somehow, miraculously, succeeds.

The Vietnamese have a phrase: "anh yêu em." Literally, it means "I love you." But "anh" implies an older brother loving, while "em" suggests a younger sister being loved. There's protection built into the grammar, hierarchy encoded in the romance. Try explaining that to someone who thinks love is just love.

Arabic has over fifty words for love, each one mapping a different shade of desire or devotion. Sanskrit distinguishes between the love that binds and the love that liberates. Japanese separates romantic love (koi) from familial love (ai). Meanwhile, English, this blunt instrument I'm using right now, gives us one word to cover everything from how I feel about coffee to how I feel about the woman I’ve never spoken to with mortal words.

My grandmother and I don't need fifty words. We don't even need one.

But poets do.

Because poetry is what happens when love overflows its containers, when feeling exceeds language so violently that new forms must be invented to hold it.

That's what I'm dragging you through in this global tour of romantic verse. Not some academic survey of "how different cultures express love."

This is about how humans everywhere have wrestled with the impossibility of attempting to define love, and the beautiful pieces of art they created as a result.

From Chinese poets getting drunk on moonlight to Persian mystics getting high on God, from African praise-singers to Aztec philosopher-kings watching their empires fall, everyone who's ever loved has faced the same crisis: words aren't enough. They never were. They never will be.

But we keep trying. We have to. Because the alternative—silence—means letting love die unwitnessed.

My grandmother is in her 80s now. We still can't talk about anything real. But last week, I published a love poem on a site she'll never read, in a language she barely speaks, about a feeling we both know.

That's all poetry has ever been. Throwing bottles into the ocean, hoping love finds a way to wash ashore in someone else's heart.

Let me show you how every culture on Earth has tried and failed and succeeded at this impossible translation. Let me show you how love poetry, in all its forms, is really just humanity's longest-running attempt to have the conversation I can't have with the woman who taught me what love looks like without ever saying the word.

Classical Asian Romantic Poetry

ADHD nearly destroyed my childhood. While other kids sat still in class, my brain ran marathons in place. Teachers called me disruptive. My mother called me difficult. And maybe the pills might’ve worked had they been prescribed. But they never were. And I tell you this because it took me thirty years to understand why Asian poetry smooths out the knots in my overactive brain.

These cultures figured out something my Western education never taught me: sometimes the only way to hold something vast is to make the container tiny.

Last month, I was working on a minimalist painting: three black lines on white canvas. For the first time in maybe ever, my mind went completely quiet. No racing thoughts. No competing voices. Just my breath and the brush and the specific weight of silence.

That's what Li Bai did in 8th century China when he wrote:

"The jeweled steps are already quite white with dew,

So late, the rose-silk curtains have not been dropped.

Through the clear crystal pane she watches the autumn moon."

Four lines. That's all. But inside those four lines lives an entire night of waiting for someone who isn't coming.

Li Bai doesn't tell us the woman under the moon is heartbroken. He shows us the dew accumulating while she forgets to lower the curtains, too fixated on the moon to notice time passing.

The poem holds her vigil without naming it.

This is emotional minimalism as a survival strategy.

When you can't process the whole feeling, when it's too large and wild to wrestle into words, you capture one perfect detail and let it represent everything else. The dew. The curtains. The moon. The unbearable weight of absence compressed into an image.

I spent years writing sprawling, messy poems about my coffee shop crushes, trying to capture some girl's laugh or the way she tucked her hair behind her ear. Meanwhile, 9th-century Japanese poet Ono no Komachi demolished me with this:

"Did you come to me,

or I to you?

I cannot tell.

Was I awake or sleeping?

Was it real or was it a dream?"

Twenty-five words. The entire disorientation of desire is mapped in less space than a good morning text.

Komachi understood what took me decades to learn: confusion IS the content. You don't explain the vertigo of new love; you recreate it in the reader's body.

The Japanese even created a specific form for this emotional compression: the tanka. Five lines, thirty-one syllables, entire universes of feeling. Here's one from Ki no Tsurayuki that still mesmerizes me:

"When I see the first

new moon, faintly marking

the twilit sky,

I think of all the months and years

that have passed by, and feel my age."

That's your youth evaporating up and into each twilit sky, in only thirty-one syllables.

But my favorite has to be Kalidasa, the 5th-century Indian poet who turned separation into weather patterns. His "Cloud Messenger" follows a yaksha (nature spirit) banished by his wife, who recruits a passing cloud to carry his love across an impossible distance:

"I see your body in the sinuous creeper, your gaze in the startled eyes of deer,

your cheek in the moon, your hair in the plumage of peacocks,

and in the tiny ripples of the river I see your sidelong glances,

but alas, my love, nowhere do I see you whole."

This is what happens when loss rewrites your entire perceptual system. Every beautiful thing becomes a fragment of the beloved, a painful reminder of wholeness now fractured.

I know this feeling.

Every song on the radio becomes about them. Every couple on the street becomes a personal insult. The whole world reorganizes itself around an absence.

Here's what Asian poetry taught me that therapy couldn't: sometimes healing isn't about processing every feeling. Sometimes it's about finding the one image precise enough to hold what can't be said. The moon through a window. Dew on stone steps. A cloud drifting north while you're forced south.

My grandmother does this without thinking. When she can't find the English words for how she feels, she touches my face. One gesture, perfectly placed, worth more than any sentence. That's the Asian poetic tradition: trusting the image over explanation, the gesture over the speech, the fragment over the whole.

These poets weren't minimalists because they lacked words. They were minimalists because they understood something it took me three decades and a nearly-fatal addiction to learn: sometimes you can only say the biggest things by saying almost nothing at all.

Every time I paint now, I think about Li Bai drunk on moonlight, Komachi dizzy with desire, Kalidasa sending clouds as messengers. They knew what my racing brain couldn't grasp: the way to hold infinity is to stop trying to hold it. Let it move through you. Catch what you can. Leave space for what escapes.

That space? That's where the poetry lives.

Key Poets to Explore:

Chinese Masters

- Li Bai (701-762) - Tang Dynasty master of emotional landscapes and impossible yearning

- Du Fu (712-770) - Intimate personal reflections amid political chaos

- Li Qingzhao (1084-1155) - Song Dynasty's greatest female voice, devastating in her precision

Japanese Voices

- Ono no Komachi (825-900) - Heian period's most celebrated female poet, unflinching about beauty's decay

- Murasaki Shikibu (973-1014) - Author of The Tale of Genji, pioneer of psychological romance

- Izumi Shikibu (976-1030) - Passionate tanka exploring forbidden love and spiritual longing

Indian Classics

- Kalidasa (4th-5th century) - Sanskrit master who turned separation into cosmic drama

- Bhartrhari (5th century) - Philosopher-poet exploring love's spiritual dimensions

- Amaru (7th century) - Erotic verse that influenced centuries of Sanskrit love poetry

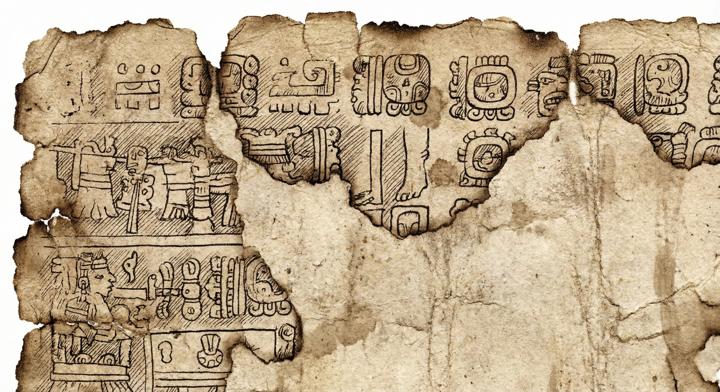

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican Love Poetry

Not being connected to American culture because my family is from Mexico was difficult for me. And not being connected to Mexican culture, because I was born in America and couldn’t speak Spanish just as difficult. Growing up, it was just embarrassing. Now, as an adult,t I’ve learned there’s an even darker meaning

Here's what they don't teach you in school: the Spanish didn't just tyrannize and enslave bodies. They attempted subjugation of emotion itself. They burned indigenous codices, banned native languages, and declared indigenous love poetry "demonic." They wanted to kill the way people felt, not just how they lived.

And yet, the poetry survived.

Nezahualcoyotl, the 15th-century Aztec poet-king of Texcoco, wrote this while watching the Spanish approach:

"I love the song of the mockingbird,

Bird of four hundred voices,

I love the color of jadestone

And the intoxicating scent of flowers,

But more than all I love my brother, man."

Read that again. This isn't some noble savage writing pretty nature poetry. This is a king who sees death approaching and chooses to document what matters: the mockingbird's song, jade's specific green, flowers that intoxicate, and above all, human connection. He's making a list of what's worth remembering when memory itself is under attack.

The Spanish destroyed 90% of indigenous texts. Ninety percent. Imagine if someone burned 90% of your memories, but you somehow held onto a few fragments. That's what we have left of Mesoamerican poetry. Fragments that survived because they were hidden, memorized, and sung in secret.

What survived tells us everything about what mattered. Like this Mayan fragment:

"You are the turkey hen

who is proud among the cocks.

You are beautiful to see,

but all you know how to do is scratch."

That's a love poem. To a difficult woman. Written by someone who sees her clearly: vain like a turkey hen, beautiful but destructive. But dammit, he loves her anyway. The specificity of his refusal to idealize while still admiring is love communicating with us through indigenous humor. That's the kind of honesty that survives conquest because it's too true to die.

The Aztecs had a word: "tlazohcamati." It means "thanks" but literally translates to "I bow to the love in you." Every thank-you was an acknowledgment of love. They didn't separate gratitude from affection, didn't compartmentalize feelings the way we do. When your language assumes love is present in every interaction, how do you write love poetry? You write about everything.

Here's what destroys me: these poets were writing about love while their children died of European diseases, while their temples were torn down stone by stone, while their gods were declared demons. They kept writing about flowers and jade and birds with four hundred voices because beauty was resistance. Documenting love was a way of saying, "You can kill us, but you can't kill what we felt."

I think about my grandmother, born in a Mexico that barely remembers these poets, speaking a Spanish that replaced their languages. The project worked so well that we lost our own words for love. But something survives in the gestures, in the way she touches my face, in the specific silence between us that holds what words can't.

When I read translations of Nahuatl poetry, I hear rhythms I recognize from somewhere deeper than language:

"We only came to sleep,

We only came to dream,

It is not true, it is not true

That we came to live on earth."

That's not fatalism. That's the voice of someone who knows everything can be taken except the dream, except the song, except the love that exists between sleeping and waking. It's the voice I hear in every recovery meeting when someone says, "I shouldn't be alive, but here I am."

The Mayans wrote their books on bark paper. They dissolved in humidity. The Aztecs carved poems into stone. The Spanish ground them to powder. But the words survived in the mouths of grandmothers, in songs disguised as Catholic hymns, in stories told after settlers went to sleep.

These fragments of pre-Columbian love poetry aren't museum pieces. They're survival guides. They teach us that when your world ends, through conquest or addiction or heartbreak, you document beauty. You praise the mockingbird. You name what you love. You write it down even if they burn the books, because someone, somewhere, will remember the words.

That's what it means to be indigenous to nowhere, to love across languages you don't speak: you become a fragment yourself, a partial translation of something older and truer than conquest. You survive by singing, even if you only know ten words of the song.

The mockingbird has four hundred voices. I only need one. It says: we're still here, we still love, we still remember, we still sing.

That's enough. That has to be enough.

Key Poets to Explore:

Aztec Voices

- Nezahualcoyotl (1402-1472) - Poet-king of Texcoco, master of love's impermanence

- Tlaltecatzin - Prince of Cuauhchinanco, known for passionate personal verses

- Aquiauhtzin - Nobleman whose fragments survive in the Cantares Mexicanos

Mayan Traditions

- The Popol Vuh poets - Anonymous creators of cosmic love narratives

- Chilam Balam scribes - Preserved Yucatecan romantic prophecies and songs

- Dresden Codex contributors - Mathematical precision applied to emotional cycles

Note: Most Mesoamerican poetry survives anonymously, filtered through Spanish colonial transcription. Seek out the Cantares Mexicanos and Romances de los Señores de la Nueva España for authentic voices.

African Romantic Oral Traditions

They kept trying to kill this poetry. It survived anyway.

Sound familiar?

I'm talking about African oral traditions, but I could be talking about my own story. The system that wanted me dead at 19—cops, dealers, my own desperate need for oblivion—now a distant memory. The poetry I scribbled in rehab, shaking from withdrawals? It outlived the notebooks I wrote it in. Without permission or approval. Because I wasn’t looking for social satisfaction or attention. I just needed to survive.

African love poetry did the same thing on a continental scale. No written permission. No academic approval. No library cards. Just voices carrying love across generations like a virus that builds immunity instead of breaking it down.

Here's what they don't teach you in your MFA program (or they might, I never got one after all): most of the world's poetry was never written down. It lived in throats and memories, in the space between speaker and listener, in the electric moment when someone says exactly what you need to hear, exactly when you need to hear it.

I loathed recovery and 12-step language when I got to rehab. It infuriated me. I couldn’t take it seriously (fifteen years later at the time of this writing, sometimes I still can’t).

So thank God for the old drug-worn ex-cons I met in there, like Anthony: an older black dude from the south who was missing most of his teeth, living in a body wrecked from spending most of his 50-something years of life in prison. He pulled me aside one day and told me I reminded him of his son, who was a teenager when Anthony first went to prison. His son nosedived right into a criminal lifestyle and overdosed at 19. The same age I was in that moment. That had been 30 years ago. And yet here Anthony was, pushing 60 and still trying to survive. “You got the choice right now,” he said. “We both got the choice, son. Because it’s never too late—it ain’t ever too late until you’re dead.” That's oral tradition. That's poetry that matters more than any sonnet.

The Yoruba of Nigeria have a saying: "Ẹni sọ̀rọ̀ lórí àpáta, ọ̀rọ̀ rẹ̀ ò ní parun." The one who speaks on the rock, their words will never perish. They understood something we've forgotten in our screenshot culture: the most important words aren't the ones you can copy-paste. They're the ones that change shape every time they're spoken, staying true while staying alive.

Take "The Song of Lawino," composed by Ugandan poet Okot p'Bitek in the 1960s but drawing on Acholi oral traditions centuries old. Lawino roasts her husband Ocol for abandoning their culture:

"Listen, Ocol, my old friend,

The ways of your ancestors

Are good,

Their customs are solid

And not hollow

They are not thin, not easily breakable

They cannot be blown away

By the winds

Because their roots reach deep into the soil."

This isn't just a woman scorning her westernized husband. This is documentation of cultural PTSD, of what happens when oppression sleeps next to you in bed and makes you wake up each day to hate your own reflection. Lawino's anger is love inverted: she's furious because she remembers when Ocol found her beautiful before he learned to see through white eyes.

But here's what kills me: Lawino's not begging. African oral traditions rarely beg. They state. They witness. They assume dignity even when describing devastation. Like this Yoruba love poem:

"Money cannot buy a child,

Money cannot buy a mother,

Money cannot buy sleep,

The love of my beloved—

Can money buy that?"

Four things the market can't touch. Four forms of wealth that exist outside transaction. This is an economics lesson as a love poem, philosophy as sweet talk. It's saying "I love you" by declaring love is not a commodity to be purchased by an unjust system.

In Kenya, the Gikuyu have praise poems where lovers list each other's qualities like inventory, but the inventory includes intangibles:

"She who walks like a gazelle,

She who laughs like water over stones,

She whose anger passes like afternoon rain,

She who knows my thoughts before I think them."

The Shona of Zimbabwe have a tradition called "madanha": love songs passed down from generation to generation, each singer adding their own verse. The song accumulates pain and wisdom like compound interest. Nobody owns it. Everybody shapes it. It belongs to the community the way trauma does, the way healing does, the way love does when it's real.

This is what the anthropologists missed when they called African traditions "primitive." These poets were doing postmodernism before Europe invented modernism. They understood that authorship is collective, that meaning shapeshifts, that the best poetry happens in the gap between one person's mouth and another's ear.

When enslaved Africans were taken to the Americas, they brought these traditions with them in their bodies. You can hear them in blues lyrics that repeat and revise, in hip-hop's oral dexterity, in the call-and-response of Sunday church. "Wade in the Water" isn't just a spiritual; it's coded instructions for escape, wrapped in praise. That's poetry doing what poetry does: surviving by any means necessary.

My friend told me something once that sounds like an African proverb but came from Oakland: "They can ban the books, but they can't ban the bars." She meant rap bars, but the principle goes back centuries. You can burn libraries. You can forbid languages. You can steal entire populations. But you can't stop people from encoding love and resistance in rhythm, in breath, in the pause between words where meaning multiplies.

I think about all the poetry I've lost. All the notebooks thrown away in moves, the hard drives that crashed, the perfect lines I thought I'd remember but didn't. Then I think about the poetry that survives. And not the words exactly, but the feeling. The way Anthony's broken-toothed wisdom lives in how I talk to young people in recovery. The way my grandmother's wordless love influences how I show affection to the people I care about. The way African ancestors survived the unspeakable and still found breath to sing love songs.

That's the real oral tradition: not the anthropological specimens in academic journals, but the living poetry that passes between us every day. The compliment that saves someone's life. The story that helps someone stay sober. The love poem spoken once at 3 AM that changes everything, even though nobody wrote it down.

African oral traditions teach us that poetry doesn't need permission to exist. It doesn't need ISBN numbers or Instagram likes or MFA workshops. It needs what it's always needed: one person with something to say and another person who needs to hear it.

They tried to kill this poetry. It survived anyway. It's surviving right now, in this sentence, as you read it and make it yours. That's the tradition. That's the love that refuses to die.

Key Poets to Explore:

Contemporary Voices Preserving Tradition

- Okot p'Bitek (1931-1982) - Ugandan poet who transformed oral tradition into written power

- Kofi Awoonor (1935-2013) - Ghanaian master of Ewe praise poetry and modern verse

- Mazisi Kunene (1930-2006) - Zulu epic poet who bridged ancient and contemporary forms

Traditional Forms to Discover

- Yoruba Oriki - Praise poetry tradition from Nigeria, celebrating love through genealogy

- Sotho Lithoko - Southern African praise songs that include romantic elements

- Swahili Mashairi - East African verse forms, especially from Zanzibar and coastal regions

Modern Interpreters

- Chinua Achebe (1930-2013) - Nigerian novelist whose poetry preserves Igbo romantic sensibilities

- Wole Soyinka (1934-) - Nobel laureate exploring Yoruba mythology and contemporary love

- Antjie Krog (1952-) - South African poet bridging Afrikaans and African traditions

Middle Eastern Romantic Poetry

In your yoga class when they quote Rumi, the 13th-century Persian religious scholar and poet do they talk about the way he was writing about spiritual transcendence the way addicts write about drugs? He found something that dissolved his ego so completely that regular life became unbearable.

I know that dissolution. I found it first in a needle, then in a bottle, then in a woman, then in a notebook, where it all came out eventually. The Sufi poets found it in divine love. Different delivery system, same high.

The Middle East gave us poetry that treats love like religion and religion like love until you can't tell the difference and maybe that's the point. These mystics wrote about the annihilation of self centuries before I discovered the same thing in my girlfriend's shower with too much heroin in my veins.

Take Hafez, the 14th century Persian master who wrote:

"I have learned so much from God

That I can no longer call myself

a Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Buddhist, a Jew.

The Truth has shared so much of Itself with me

That I can no longer call myself

a man, a woman, an angel, or even a pure soul.

Love has befriended me so completely

It has turned to ash and freed me

Of every concept and image my mind has ever known."

That's not poetry. That's a trip report. That's someone documenting complete ego death and rebirth. When Hafez says love "turned to ash" every concept he had, he's describing "deflation of ego at depth." He's describing what happened to me when I finally surrendered to the fact that I couldn't control anything, especially not love.

The Persian poets invented the ghazal, a form built on obsessive repetition. Same phrase ending every couplet, like your brain stuck on the same thought. Like praying the same prayer until the words lose meaning and become pure sound. The repetition isn't a bug; it's the feature. It mirrors how obsession actually feels.

Here's Hafez again:

"Where is the door to the tavern? I'm done with the mosque.

Where can I find what the preachers have lost in the mosque?

I've spent years worshipping worship itself in the mosque.

Now I want the wine they've declared unholy in the mosque."

That refrain—"in the mosque"—hits like a hammer. Four times in four lines. By the end, the mosque becomes a prison and a place of salvation. That's how love works when it's the addictive kind. You know it's killing you, but it's also the only thing keeping you alive.

The Arabic tradition goes further. Pre-Islamic poets would literally start their poems by standing in the ruins of their beloved's abandoned campsite, weeping over places where tents used to be. They called it "wuquf 'ala al-atlal"—stopping at the ruins. Imagine being so torn up about your ex that you travel to where they used to live and just cry over the empty space.

But I get it. I've done it. Drove past the coffee shop where she used to work, even after it closed. Sat in the parking lot like an idiot, manufacturing grief from geography. The Arabs knew: landscape holds emotion. Places remember even when people forget.

Imru' al-Qais, the 6th century badboy of Arabic poetry, opens his most famous poem:

"Stop, let us weep at the remembrance of a beloved and an abode

In the sand-hills between Dakhool and Hawmal,

Where the south wind blows the sand over the traces

And the north wind spreads it again."

He's not just being dramatic. He's showing how memory works; the south wind covers the traces (time heals!), but the north wind reveals them again (just kidding!). The desert becomes a metaphor for consciousness, constantly hiding and revealing the ruins of love.

But the real genius is Ibn Arabi, the 13th century mystic who said I'm going to love everything:

"O Marvel! a garden amidst the flames.

My heart has become capable of every form:

It is a pasture for gazelles and a convent for Christian monks,

And a temple for idols and the pilgrim's Kaaba,

And the tables of the Torah and the book of the Quran.

I follow the religion of Love: whatever way Love's camels take,

That is my religion and my faith."

This is advanced-level recovery. This is Step 11 ("sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact"). Ibn Arabi's heart contains contradictions because love obliterates the boundaries that keep contradictions separate. When he says his heart is both "a garden amidst the flames," he's describing what it feels like when destruction and creation happen simultaneously.

I felt this in early sobriety when everything hurt, but I was grateful for the hurt because it meant I was alive to feel it. The Sufis called this state "fana"—annihilation in the divine. We call it ego death. Same transformation, different vocabulary.

The Middle Eastern tradition gave us poets who weren't afraid to compare romantic love to spiritual intoxication because they understood both were about surrendering control. They wrote about love the way addicts talk about their drug of choice: with reverence, terror, and the knowledge that it will probably kill them but at least they'll die fully alive.

Modern Persian poet Forugh Farrokhzad carried this tradition into the 20th century:

"I will plant my hands in the garden

I will grow I know I know I know

and swallows will lay eggs

in the hollow of my ink-stained hands."

She's not just gardening. She's saying creativity and love require the same thing: planting yourself in uncertainty and trusting something will grow. The "I know I know I know" is mantra, prayer, and desperate hope all at once. It's what we repeat when we don't know but need to believe.

This is what Middle Eastern poetry teaches: love is intoxication, but holy intoxication. Love is addiction, but addiction to something that expands rather than contracts you. Love is annihilation, but annihilation that reveals who you really are when all the darkness burns away.

My grandmother prays the rosary every night. I don't know what she prays for (probably for me to find a nice girl). But I know the repetition soothes her the way ghazals soothe, the way mantras soothe, the way checking your phone soothes until it doesn't.

The Middle Eastern poets knew what every addict knows: sometimes you need to get out of yourself to find yourself. Sometimes you need to repeat the beloved's name until it becomes meaningless and then becomes everything. Sometimes you need to follow love's camels wherever they lead, even if it's straight into the desert.

They wrote about love like mystics because love is mystical. They wrote about it like addicts because love is addictive. They wrote about it like believers because what else is worth believing in?

Key Poets to Explore:

Arabic Foundations

- Imru' al-Qais (6th century) - "Father of Arabic poetry," master of the pre-Islamic qasida

- Qays ibn al-Mulawwah (7th century) - "Majnun Layla," the archetypal mad lover

- Omar Ibn Abi Rabi'ah (644-719) - Umayyad playboy whose verses scandalized and enchanted

Persian Mystics

- Rumi (1207-1273) - Sufi master who transformed earthly love into divine ecstasy

- Hafez (1315-1390) - Shiraz's greatest voice, perfecting the ghazal form

- Saadi (1210-1291) - Author of The Rose Garden, master of both sacred and profane love

Modern Voices

- Nazim Hikmet (1902-1963) - Turkish revolutionary whose prison letters redefined romantic urgency

- Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008) - Palestinian poet who made homeland and beloved inseparable

- Forugh Farrokhzad (1935-1967) - Iranian feminist who shattered traditional Persian romantic forms

European Romantic Traditions

Every generation thinks it invented rebellion. Every generation is wrong.

I learned this the hard way when I started copywriting. Thought I was hot shit, breaking all the rules, writing vulnerability into sales pages, telling stories instead of listing benefits. Then my mentor, Jennifer, showed me I was just using formulas I didn't even know existed. "You're not breaking the rules," she said. "You're following older ones."

Same thing with European love poetry. Every movement screams "Death to the old ways!" while standing on the shoulders of whoever they're supposedly killing. It's like recovery: you think you're unique until you hear your exact story from someone who got clean in 1973.

Start with the troubadours. In 12th-century southern France, these poor saps invented the idea that suffering for love makes you noble. They'd travel castle to castle, singing about how Lady Whatever wouldn't sleep with them, and somehow made not getting laid into high art.

Bernart de Ventadorn, patron saint of the friend zone, wrote:

"When I see the lark beating

Its wings joyfully against the sun's rays,

Forgetting itself and letting itself fall

With the sweetness that enters its heart,

Alas! Such great envy comes to me

Of those I see rejoicing,

I wonder that my heart

Does not melt from desire."

He's watching a bird have a better time than him. The lark gets to surrender to joy while Bernart's stuck on the ground, cockblocked by the entire feudal system. But here's the genius: he made sexual frustration spiritually noble. He transformed "she won't sleep with me" into "my suffering purifies my soul."

Every Nice Guy in history owes these troubadours royalties. They invented the idea that wanting someone who doesn't want you back makes you deep, not creepy. They created courtly love; they’re the blueprint for every coffee shop poet writing about their barista who definitely isn't interested.

(Yes, I’m talking about myself. I have three notebooks full of poems about a girl who made my lattes and never learned my name. I called it "Songs for the Siren of Sunset Boulevard." She called it "her job.")

Then came Petrarch in the 14th century, who took the troubadour formula and added mathematical precision. The sonnet: fourteen lines, strict rhyme scheme, turn at line nine. It's like he invented the poetry equivalent of CrossFit with unnecessary constraints that somehow produce results.

Petrarch spent 40 years writing about Laura, a woman he allegedly saw once in church. 366 poems about someone he never had a conversation with. A parasocial relationship. That's me writing about that tattooed model from Instagram who liked one of my posts in 2019.

But here's why it works: the form contains the obsession. Those fourteen lines become a pressure cooker for feeling. By the time you hit the final couplet, the emotional compression creates diamonds. Or at least cubic zirconia that looks real in the right light.

Shakespeare took Petrarch's form and said "What if I made it dirty?" Sonnet 130: "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun." He's talking trash in iambic pentameter. He spends twelve lines obliterating his girl. She doesn't smell like perfume, she walks heavy, her voice isn't music—then hits you with:

"And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare."

Honesty in love. "I see you clearly, flaws and all, and choose you anyway." Shakespeare broke the rules by admitting the truth: real love isn't about perfection. It's about specificity. It's about loving someone's actual morning breath, not the idea of their rose-petal mouth.

Fast-forward to the Romantics, who decided emotion should be BIGGER. MORE. EXTREME. These were the first poets to make mental illness seem sexy. Byron slept with his sister and made it seem like it was brooding. Shelley abandoned his pregnant wife for a teenager and wrote beautiful verses about it. Keats died at 25, writing letters to Fanny Brawne that sound like they were composed on cocaine:

"I have been astonished that Men could die Martyrs for religion—I have shudder'd at it—I shudder no more—I could be martyr'd for my Religion—Love is my religion—I could die for that—I could die for you."

This is your brain on Romanticism. Everything is life or death. Every feeling is ultimate. It's exhausting and intoxicating, and I recognize it from my worst relationships. The ones that felt like everything when they were really just endorphins dressed up as enlightenment.

But the Romantics gave us permission to feel too much. They said it's okay to write forty poems about someone's hand. It's fine to compare your broken heart to the fall of civilizations. Go ahead and threaten to die if she doesn't love you back. (Don't actually die. But the threat? Poetry gold.)

Then the Victorians showed up and said, "What if we were repressed about it?" But repression creates its own intensity. When you can't say "I want to chew into your collarbone," you write about flowers trembling with dew, and everyone knows what you mean.

Christina Rossetti wrote "Goblin Market," ostensibly about sisters and fruit, actually about female desire eating you alive:

"She suck'd and suck'd and suck'd the more

Fruits which that unknown orchard bore;

She suck'd until her lips were sore;"

That's not about fruit. That's about addiction, compulsion, the way desire becomes need becomes destruction. But because it's wrapped in fairy tale drag, the Victorians could pretend it was appropriate while getting off on the subtext.

Every European generation built on the last while claiming to destroy it. The troubadours created noble suffering. Petrarch added formal precision. Shakespeare brought psychological complexity. The Romantics exploded into emotion. The Victorians compressed into code. Each rebellion became the next generation's orthodoxy.

It's like watching myself evolve as a writer. First, I copied the masters without knowing it. Then I rebelled against everything. Then I realized the rebellion had rules too. Now I use whatever works, stealing from everyone, following formulas when they serve me, breaking them when they don't.

That's what European poetry teaches: tradition and rebellion need each other. You can't break rules that don't exist. You can't innovate without understanding what came before. Even "there are no rules" is a rule.

Every love poem written today owes something to these argumentative Europeans who spent a thousand years disagreeing about how to say "I love you." We're all troubadours, whether we're posting on Instagram or publishing chapbooks. We're all trying to make noble suffering from regular suffering, to compress chaos into beauty, to find new ways to fail at saying what can't be said.

The only difference is that we do it faster now. Petrarch spent 40 years on Laura. I spent two weeks on coffee shop girl before moving on to bartender girl. Evolution or devolution? You decide.

But the project remains the same: make art from wanting what we can't have, what we had and lost, what we have but don't know how to hold. The Europeans didn't invent romantic poetry. They just showed us that rebellion and tradition are the same dance, just depends on which partner is leading.

Key Poets to Explore:

Medieval Masters

- Bernart de Ventadorn (1130-1200) - Troubadour who perfected courtly love's exquisite agony

- Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) - Transformed personal obsession into cosmic journey in La Vita Nuova

- Christine de Pizan (1364-1430) - Medieval France's first professional female writer, revolutionary romantic voice

Renaissance Innovators

- Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374) - Created the sonnet form that would dominate European love poetry

- William Shakespeare (1564-1616) - Complicated romantic idealization with psychological realism

- Louise Labé (1524-1566) - French poet whose passionate sonnets shocked Renaissance society

Romantic Era Revolutionaries

- John Keats (1795-1821) - Sensual romanticism that made physical beauty spiritual

- Percy Shelley (1792-1822) - Radical politics fused with transcendent romantic vision

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) - Sonnets from the Portuguese redefined female romantic agency

Romantic Poetry in the Americas

America's love poetry is a bastard art. That's what makes it real.

We're mutts here. Colonized and colonizer, indigenous and immigrant, enslaved and free, all fighting and falling in love with each other and writing poetry about it. Our love poems carry the DNA of everywhere else, mixed with blood spilled on this soil. Not pure; scarred.

I am the grandson of a Mexican drug dealer who was widowed by a heroin overdose. I am the son of parents who broke each other trying to build something new. And I am just another surviving addict in a Los Angeles meeting room, learning to love myself after years of evidence I shouldn't. I am American: a beautiful disaster of conflicting truths.

Our poetry sounds like that: contradiction.

Listen to Joy Harjo, Muscogee Creek Nation, writing love into landscape:

"I link my legs to yours and we ride together,

Toward the ancient encampment of our relatives.

Where have you been? they ask.

And we answer, the years are nothing.

We have been riding out on the stolen horses of our ancestors,

Heading toward the edge of the world."

She sees love despite apocalypse, love through genocide, love as resistance to erasure. She links her legs to her beloved's, and they ride stolen horses, reclaiming what was taken, making love on the bones of loss.

Luci Tapahonso answers by grounding love in the physical. Not universal "mountains" but these particular peaks. Not generic "morning" but this exact dawn:

"This morning when I woke

beside you, I remembered

how as a child I walked

the path to my grandmother's

before sunrise, and the world

was mine alone—

until now, lying here

with you, the same stillness

holds us both."

She connects childhood's solo wonder to adult intimacy, but the bridge between them is landscape. It’s the same paths, the same silence, the same New Mexican morning. Her love exists in place, inseparable from the land that holds it. That's indigenous love poetry: rooted deeper than conquest can reach.

Meanwhile, Black Americans were creating poems about love from the fragments of languages they weren't allowed to keep. Stripped of their original tongues, they made English jump through hoops it never knew existed. They took the master's language and made it moan.

Langston Hughes laid it down plain:

"Love is a ripe plum

Growing on a purple tree.

Taste it once

And the spell of its enchantment

Will never leave."

Simple words carry complex history. The plum evokes beauty despite terror, sweetness earned through suffering. Hughes doesn't need to explain how love feels different. The plum knows. The purple tree remembers. The enchantment carries both pleasure and pain.

But it's Gwendolyn Brooks who really shows how Black love poetry reinvents English:

"Exhaust the little moment. Soon it dies.

And be it gash or gold it will not come

Again in this identical disguise."

"Gash or gold": love as wound or treasure, maybe both at once. Brooks makes English a percussion instrument, all those hard consonants crashing together. She's not writing in the settler’s language; she's writing in jazz, using words like Coltrane used notes.

Then there's my people, the in-between people, the hyphenated Americans writing love in Spanglish. Julia de Burgos saw it clear:

"You are like my soul, so restless and so free,

That to attempt to hold you would be like

Grasping the wind or binding the sea."

She's writing in English but thinking in Spanish, where wind and sea have gender, where restlessness is a virtue, not a flaw. Her love poetry exists in the gap between languages, saying what neither tongue alone can hold.

This is what I inherited: love poetry shaped by multiple languages simultaneously. It carries conquest and resistance in the same line birthing beauty from cultural collision.

It’s not hard to understand Pablo Neruda when he writes:

"I love you without knowing how, or when, or from where,

I love you directly without problems or pride:

I love you like this because I don't know any other way to love,

except in this form in which I am not nor are you,

so close that your hand upon my chest is mine,

so close that your eyes close with my dreams."

Even in translation, it connects. Because Neruda wrote from the intersection of old world and new, Spanish and something else, tradition and “screw the tradition.” He made the sonnet Latin American by filling it with chile and clay instead of roses and marble.

But here's what makes American love poetry different from everywhere else: we're not trying to be pure. We can't. We're the mixed kids at the global poetry party, taking what we want from every tradition, making something new from the wreckage.

Native American poets write love through genocide's aftermath. Black poets write love through the echo of slavery. Latino poets write love through borders and barriers. Asian American poets write love through exclusion acts and internment camps. And somehow, from all this historical trauma, comes the most innovative love poetry on the planet.

Because we learned what the pure traditions couldn't teach: love isn't separate from history. It's not some universal feeling floating above politics and pain. Love happens in specific bodies in specific places with specific scars. That's American love poetry: gorgeous mongrel verses that refuse to pick a side. We write in English haunted by Spanish, in forms borrowed from Europe but bent toward justice, in rhythms stolen from Africa and given back as a gift.

That's why American love poetry matters: because we're proof that beautiful things grow from broken ground. That love finds a way even when they steal your language, even when they split your culture, even when you can't talk to your own grandmother.

We write love poetry like we live—improvising, surviving, making it up as we go. Taking what works, leaving what doesn't, creating new forms for feelings that didn't exist until history created us.

And if that's not poetry, I don't know what is.

Key Poets to Explore:

Indigenous Voices

- Luci Tapahonso (1953-) - Navajo poet connecting romantic experience to natural cycles

- Joy Harjo (1951-) - Muscogee Creek poet weaving love through tribal and personal history

- Leslie Marmon Silko (1948-) - Laguna Pueblo storyteller whose poetry grounds love in landscape

African American Pioneers

- Countee Cullen (1903-1946) - Harlem Renaissance poet transforming romantic language into cultural exploration

- Langston Hughes (1901-1967) - Jazz rhythms applied to romantic verse and social justice

- Gwendolyn Brooks (1917-2000) - First Black woman to win Pulitzer, master of intimate urban romance

Latino/Hispanic Traditions

- Pablo Neruda (1904-1973) - Chilean Nobel laureate whose Twenty Love Poems redefined Latin American romance

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695) - Mexican nun whose baroque verses challenged colonial romantic restrictions

- Julia de Burgos (1914-1953) - Puerto Rican poet who made personal liberation inseparable from romantic freedom

North American Innovators

- Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) - Reclusive genius who compressed enormous romantic feeling into tiny verses

- Walt Whitman (1819-1892) - Democratic romantic vision that celebrated bodies and souls equally

- Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) - Feminist poet who interrogated traditional romantic structures

Romantic Poems About Love: A Cultural Human Constant

This whole journey through global love poetry? It's all been about the same impossible project: trying to say what can't be said, in languages that were never built to hold this much feeling.

The Chinese poets knew this. They compressed entire lifetimes into seventeen syllables because they understood that love is too large for language. Make the container small enough, and maybe you can hold one perfect drop of the ocean.

The Aztecs knew this. They wrote about mockingbirds and jade while conquistadors burned their libraries, documenting beauty as an act of resistance. Sometimes the only way to preserve love is to sing it into hiding.

The Africans knew this. They carried poetry in their bodies across oceans, keeping love alive in rhythm and breath when everything else was stolen. The poem doesn't need paper if it lives in your pulse.

The Persians knew this. They repeated the beloved's name until it became meaningless and then kept repeating until it became everything. Sometimes you have to break language to let love through.

The Europeans knew this. Each generation rebelled against the last while secretly building on its foundations. We all pretend we're inventing love when really we're just finding new ways to fail at the same translation.

The Americans know this. We're all orphans here, making family from fragments, writing love in languages we half-remember or never knew. Our poetry sounds like beautiful damage because that's what we are.

But here's the truth I'm just now learning: the failure is the point.

If I could perfectly translate what my grandmother means to me, if I could capture it completely in words, then the words would be bigger than the love. And they're not. They never will be. The gap between what we feel and what we can say is where poetry lives.

My grandmother doesn't need to read my poems to know what they're about. She's known all along. Every time she touched my face. Every time she fed me. Every time she slipped me twenty dollars when I tried to refuse. Every time she looked at me with those eyes that spoke in a language deeper than Spanish or English or any sounds humans make.

She knows I love her. I know she loves me. That's what all poetry is: not communication but overflow. Not translation but the record of our beautiful failure to translate. We write because we have to put the excess somewhere, or it will kill us.

When Li Bai wrote about moonlight on water, he wasn't describing the moon. He was documenting the ache of reaching for what shimmers just beyond grasp. When Rumi spun in circles writing about divine love, he wasn't capturing God. He was marking the circumference of mystery. When Langston Hughes compared love to a plum, he wasn't defining sweetness. He was naming what survives despite everything.

Every love poem ever written is the same poem: "I cannot say this but I must try."

That's why we need poetry from every culture, every tradition, every voice. Because each attempt fails differently. Each language breaks in its own specific way. Each culture develops its own techniques for beautiful failure. Together, they form a map of the untranslatable; not showing us where to go, but showing us we're not alone in being lost.

My grandmother will die without us ever having had a real conversation. I'll never be able to explain how she saved me by loving me when I was unlovable. I'll never find the words for how her silence taught me more than any sermon. I'll never adequately translate what passes between us in the pressure of held hands.

But I'll keep trying. We all will. That's what humans do.

We fall in love. It breaks us open. Words pour out like blood from a wound, except the blood is song and the wound is just another word for door. We write poems on napkins and phones and cave walls and hospital bedsides, trying to name what has no name, trying to hold what can't be held, trying to translate the untranslatable fact of loving another person in this brief, impossible life.

The poems always fail. They have to. Love is bigger than language, older than words, deeper than any sound we've learned to make. But somewhere between the attempt and the failure, something happens. Someone else reads our botched translation and whispers "yes, exactly." Not because we succeeded but because our specific failure mirrors theirs. Because our broken words fit their broken silence.

That's the miracle. Not that poetry captures love, but that it captures the trying. Not that we can translate between languages,s but that we keep attempting it, keep throwing these bottles into the ocean, keep faith that somewhere, someone will pick up our scrambled message and understand not what we said but what we couldn't say.

We are all translators without dictionaries, all poets without language, all lovers without words adequate to our love.

We speak different tongues but share the same silence. We write different poems but document the same impossibility. We fail in different ways but succeed in the only way that matters:

We try.

Despite the futility. Because of the necessity. With the faith that somewhere, in some language we haven't invented yet, there exists the perfect word for this feeling. And until we find it, we'll keep writing.

That's enough. That has to be enough.

And somehow, miraculously, it always is.